After attending Lorena Germán’s Coffee and Conversations session on meaningful inclusion of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) in the classroom and in curriculum, SAP team members Joy Delizo-Osborne, Pascale Joseph, and Carey Swanson reflected on some of the questions raised during the session, their own personal and professional experiences with this topic, and how educators might involve families in this work. In this series of posts, Joy discusses the importance of intersecting the Shifts with discussions about anti-racism, Pascale reflects on her love of reading as a student, and Carey shares how incorporating mirrors and windows in curricular materials may have made a difference to her students.

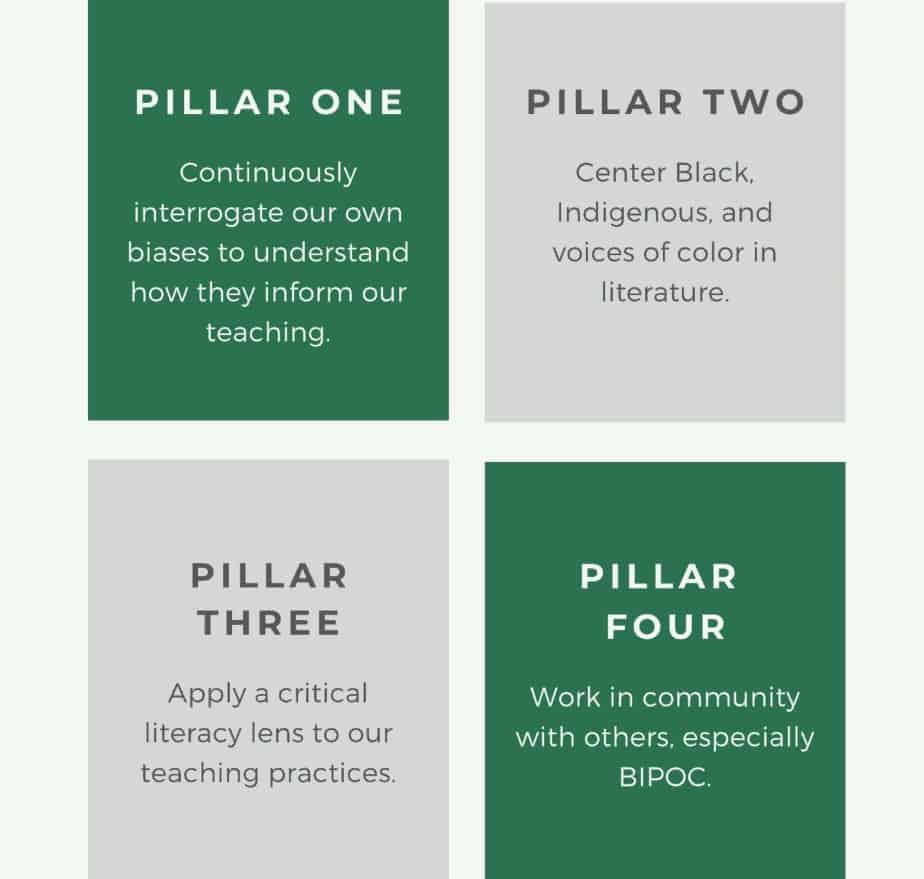

Over the past several years I’ve been reading and reflecting about the way race, privilege, and aspirational anti-racism intersects with my identities as a white woman, mother, person, and literacy specialist. I had the opportunity to attend Lorena Germán’s Coffee and Conversations session this fall and have been thinking deeply with my colleagues about attending to the four pillars presented by the founders of Disrupt Texts, starting with interrogating my own biases in my role and my work. Here are some reflections.

What unique identities or perspectives do you bring to this discussion?

I believe passionately in the potential power of the written word and how that power can be wielded for transformation by students in the classroom. I was born and raised in Michigan, in a middle-class white household, to a Jewish mother and Christian father. Outside of my mixed religious background, while growing up, I did not strongly identify with a specific aspect of my background in a way that I could articulate. However, I always saw myself as a reader, and harbored a life-long and wide-ranging love of fiction books—those that gave me insights into other time periods or places, as well as those that showed me versions of characters that looked like me, or embodied experiences that were familiar to me. Growing up I could often be found reading under my blanket late at night. I was always a bookworm, and as I grew older, I intentionally used reading as a way of learning about others, taking on the tone of an author in my head after reading a text with a new or different voice. As a parent, one of my greatest joys is reading to my children. I began by choosing a wide range of texts and now they choose them too, begging for “just one more chapter” as we read before bed at night.

I took this love of reading with me into the classroom as a teacher, and I can name so many students I watched latch on to reading and pour themselves into the pages of books. I started teaching in the early 2000s and recently have been looking back on that time with the clarity of vision that hindsight affords. Disrupt Texts cofounder Tricia Ebarvia notes, “it’s often our personal identities and experiences that have the most profound effects on our teaching, and that which often—and most dangerously—go unexamined.” As I engage in this personal reflection now, I find myself wishing that as a young teacher, I had thought more critically about my own identity as a white teacher of primarily Black students and the mindsets, perspectives, and experiences that afforded me. Doing so would have supported my ability to deeply consider my students’ identities and how we all bring our identities to the pages of the books we read.

How much more might I have offered my students if I’d deeply considered my own identity and biases? How might my students’ experiences with text have deepened if I had considered how frequently they saw themselves in text, how likely they were to identify with the protagonist’s journey, and how intentionally I was supporting students in engaging with what Rudine Sims Bishop coined as “mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors“? As a parent and an educator, I’m mindful of how important this work is, and how I need to make adjustments to my work and my thinking to attend to this with intention and precision.

What does disrupting the canon mean to you?

The work of disrupting the canon, to me, means going beyond interrogating biases and building onto the other three pillars while considering ways to expand upon texts, topics, and stories that have historically been centered in the classroom. It is a way to ensure that Black, Indigenous, and students of color are affirmed and not marginalized in texts. This work is important no matter the racial composition of your classroom. In my work now, I support educators to incorporate the ELA Shifts of complexity, evidence, and knowledge in their classrooms. These Shifts to literacy instruction have the potential to be transformative; they are necessary Shifts, but they are not sufficient on their own. There are many wonderful folks in the field to learn from here in order to do and scale this needed work. I’m thinking deeply about how to find—and support educators to find—the sweet spot where Shifts-aligned ELA instruction intersects with what Django Paris calls “culturally sustaining pedagogy.” Tricia Ebarvia provides support here by presenting questions we can ask ourselves about how our experiences inform our practice.

|

As I read to and with my own children, I’m asking myself these same questions. I recognize that their literacy experiences, the development of their own anti-racist perspectives, and the ways in which they can be exposed to the windows and mirrors of text and the critical lens needed to interrogate them can be much different, either by the choices I make or those made for and with them at school.

What resources or suggestions do you have for teachers to share with families about this work?

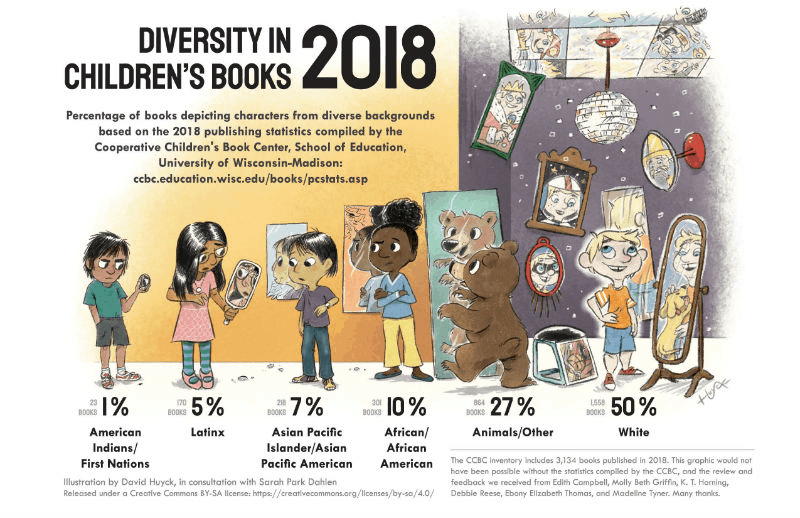

Start by considering the identities of the students and families in your class community. Who is present? Do they see themselves positively affirmed in the texts you use in your classroom? Work in community with parents and caregivers here, reaching out to them not just to build relationships but also to ask, “what books do you love and want to have read to and with your child?” If centering BIPOC authors and stories in your classroom library is a need, there are ample resources online with suggestions for how to do that. Consider not only using them as a teacher but also sharing them with families—swap a suggested home reading list with We Need Diverse Book’s “Booktalking Kit” or Here Wee Read’s “Ultimate List of Diverse Children’s Books.” Think beyond simplistic representation and look closely at the authors, character, and content.

Don’t stick to just mirrors, especially if your class makeup is homogenous. Windows are the primary way in which children learn to consider the identities, backgrounds, and experiences of others. If you are worried about potential family resistance or pushback, approach informing parents like any other content area—provide the context and information needed for parents to support their children, and teach based on what you know to be best practice. Lorena Germán talked about simply informing families: consider noting, for example, that the American Psychological Association has children’s book recommendations for various issues, such as Something Happened in Our Town as a story about the impact of a police shooting on a community, or Marvelous Maravilloso as a story about skin color, race, ethnicity, and family. Know that each child in your classroom will be exposed to texts based on the decisions that are made in their household, and by you.

Finally, leave room for growth (your own growth, as well as your community’s), and to learn from others (particularly for white educators listening, learning, and working in community with BIPOC educators, the fourth pillar by the Disrupt Texts founders). As I continue to interrogate my own work while learning from others, I’m certain that I’ll make missteps and hope to use those to do better. I’ve likely made some here in this post that you may have noticed while reading—if so, share them in the comments. While you are there, feel free to share how your identity shaped your relationship with texts as an educator, parent, or reader, or what commitments you are making in this space as an educator.