So.

Since my first blog on argument writing appeared here at Achieve the Core, our country has held a tumultuous election. That election has given many of us a lot of food for thought. It’s a good time to be thinking about argument writing!

Why?

We at the Vermont Writing Collaborative understand that the purpose of teaching students to write sound arguments is really to teach them to think deeply about substantive knowledge; to come from a habit of mind which recognizes and appreciates both complexity and the very real possibility of error; to hold a perspective that is not one of “gotcha” but rather one which values solutions that genuinely solve problems.

Good argument thinking and writing – like elections, we hope – have everything to do with a thoughtful citizenry making thoughtful decisions which help to solve real problems.

What does effective argument planning and instruction look like?

There are many ways that effective argument planning can look. Let’s look at the planning one middle school teacher, well-versed in the Writing for Understanding approach, did around the concept of wind energy and whether or not it’s a good idea – clearly a topic that requires substantial knowledge building, and an important part of her school’s curriculum.

The Big Idea and Focusing Question

First, the teacher needed to decide what Focusing Question for writing would guide students as they built their knowledge of the topic.

Here’s what she decided:

An organization in your state, Creating Sustainable Energy, is looking into the advantages and disadvantages of various types of energy for meeting the future energy needs of the state. Ultimately, it needs to make a recommendation to the state legislature about which types of energy it makes most sense to invest in.

One of those energy sources is wind. Wind power is an idea that is attractive to many people, and unattractive to others. Should our state invest money in wind energy research? Your job as the research committee is to look into the advantages and disadvantages, and to make the best recommendation you can to the CSE about whether or not to put money into wind energy research.

Building Knowledge

Next, the teacher had to decide what students would need to know about wind energy before they wrote the essay that addressed the Focusing Question, and what texts and other resources would build this knowledge. This included:

- What is wind energy and how does it work?

- Where has it been used?

- What are the advantages of wind energy? What are the disadvantages?

To build this knowledge, the teacher knew she would have to find texts from credible sources, both about the science of wind power (a degree of technical understanding) and about the advantages and disadvantages of wind power in terms of energy reliability, policy questions, aesthetic questions, and cost. Her goal would be to build deep understanding – not superficial talking points – of the issue of wind energy. Since the texts would be challenging, she also knew that she would need to guide students through the reading so that they were making meaning from the texts and building genuine domain knowledge of wind energy and the issues surrounding it (at a depth and level appropriate for middle school).

To synthesize their understanding, the teacher decided she would have her students write an informative essay (note: NOT argument yet!) on the advantages and disadvantages of wind energy. This, she thought, would help students synthesize what they knew about the pros and cons of wind energy without having to evaluate them.

Understanding Perspective

The next step, the teacher decided, would be to introduce students to a variety of perspectives on wind energy. In the real world, how people feel about various sides of a question – their personal, emotional perspective on the problem – has a lot to do with what they see as reasonable ways to solve a problem.

To help them think deeply about the different perspectives, students would write short narratives exploring each perspective. The first would be that of young boy whose family farm was saved by the rent paid by the wind turbine company. The second perspective would be that of a hardworking wildlife biologist who sees that the animal habitat is being harmed in the area of the wind turbines.

NOTE: Of course, it’s not always possible to have students write these two “along-the-way” pieces before the actual argument writing, but having them do the thinking that these two pieces capture is important and helpful.

Considering the evidence, making a claim

By this stage, this teacher realized, her students would know a lot – about wind energy itself, and about people’s personal and differing experience with wind energy. She needed to prepare them for the final task – making a claim and writing an argument.

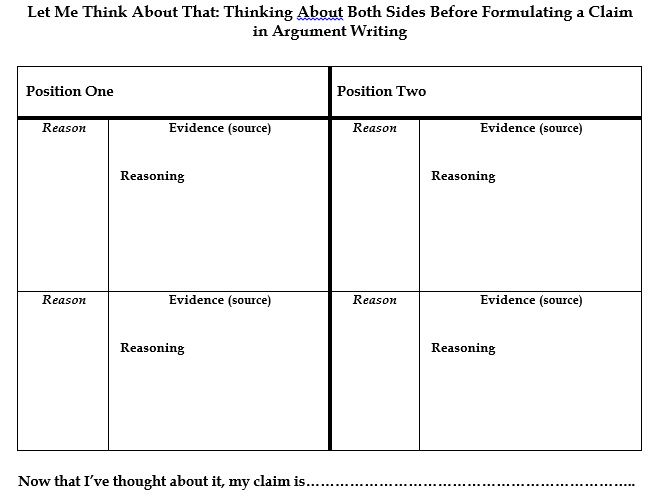

First, she created a graphic organizer (below and attached for download) for synthesizing both sides of the question.

This organizer would help the teacher lead her students through a discussion: What are the best reasons for supporting wind energy? What are the best reasons for not supporting it?

Only after this critical thinking work would students weigh the evidence: Where, in their educated, value-informed view, did the weight of the evidence lie?

That would be their claim – arrived at only AFTER building their knowledge of the topic through their reading, and carefully considering the evidence on both sides.

Structure

This teacher knew that before students sat down to write, they would need a sense of structure: What does this kind of thinking look like in clear writing? How will I know how to build this essay?

In this particular class, the teacher knew that students had already done a lot of work with expository writing structures (including lots of experience with the Painted Essay™). However, she also knew that students had not done much work with “argument thinking,” especially using a counterclaim effectively, accurately, and respectfully. She decided to write a model for her students to work with – not about wind energy (that was their task!), but about something similar, like whether or not to recommend geothermal energy development. This, she knew, would give her students a concrete understanding of both overall structure (which was familiar) and argument thinking (which was not).

Preparing for writing

Finally, it would be time for students to plan their own essays. Choosing the reasons and evidence they considered the strongest, they would develop the argument essay using the graphic organizer.

Keeping in mind that issues are rarely black and white, the teacher built in time for students to “talk their pieces” at the planning stage – before writing. She wanted to make sure that all her students had ample opportunities to construct their thinking, then rehearse it – aloud – before the final challenging task of actual thoughtful writing. She knew that considering the counterclaim was especially difficult, and so important – working with it would help students “capture the complexity” in a respectful, civil way that is a hallmark of good argument writing.

At last – writing!

The teacher decided to leave room for flexibility in this portion of the lesson to allow her to assess how she could best support her students. She could have students write the piece in chunks, stopping after each chunk to do some conferring, or she could have them write a full first draft. She knew that some of her students would need more support than others at this stage.

She decided to see how her students were managing as they undertook their study of wind energy; she would do some informal formative assessing as she went along, and decide on the best way to proceed with the writing based on that.

To sum up….

Planning for effective, thoughtful argument writing requires:

- Planning with substance in mind (e.g., wind energy matters)

- Planning with thoughtful, nuanced problem-solving in mind

- Planning for knowledge-building

- Planning for note-taking that fosters critical thinking

- Planning for “talking ideas”

Challenging and time-consuming stuff – and well worth it!