Running is hard.

Like many teachers, I prioritized grading papers, designing lessons, and returning parent phone calls before my health. My weight climbed to 240 pounds, and life-threatening ailments like hypertension and diabetes became looming possibilities. I decided to address my health and find a way to get my physical condition under control in June 2017. I knew I had to start somewhere so I started running.

Running is hard. When I decided to take up running, I had no idea where to start: Did I have the right shoes? Was I supposed to feel this out of breath? Could all my fellow runners tell I was new at this? I wanted to be successful with running—I needed to be for my health—but I needed a lot of guidance. Learning to write well is the same way.

I will never forget my first high-stakes writing assessment: it was the Mississippi Graduation Writing Test in March 1996. Although I was an A student at the top of my class, I was still afraid of this assessment because it required me to write, on demand, in order to obtain my high school diploma. The blue book was sealed by a round, white sticker. With a fresh No. 2 pencil in hand, I broke the seal, opened the book, and read the first page. Like an underprepared runner at the start line of a race, I wished I’d had more training.

With writing, the struggle to complete begins with the struggle to get started. For many students, the struggle to start writing exists because they haven’t been taught an explicit process to start writing. Here are some strategies I’ve found helpful for supporting students.

The Struggle to Get Ready

The first step in drafting any composition is pre-writing.

A blank page can be extremely daunting for a writer. Without the proper tools to begin, a struggling writer often gives up. Some of our students have no idea where to begin when given a task that requires writing. This underscores why the pre-writing process is so important.

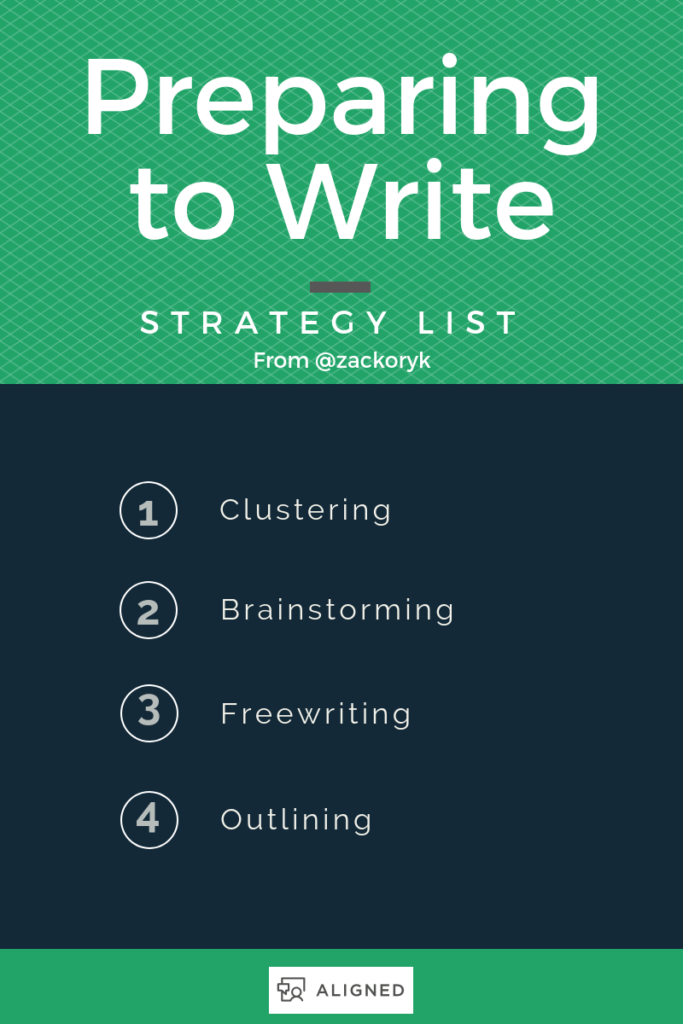

Pre-writing is the methodical process that a skilled writer follows before composing. Students must be explicitly taught this process before they can be expected to do it proficiently. Components of this process include:

- Clustering—Selecting a word central to the text or writing prompt, then brainstorming related words or ideas, can help writers who have no clue where to start to identify a direction for their writing. Here’s an example.

- Brainstorming—Setting aside time to explicitly think about what evidence, plot points, or even vocabulary might be included in a writing assignment can help do away with intimidation of the blank page. This can be done together as a class, in small groups (particularly helpful for English Language Learners), or even independently.

- Freewriting—A form of brainstorming, freewriting allows students to write freely, anything that occurs to them about the writing topic (even writing some words in their native language if they are English Language Learners). This helps get the ideas flowing. Unlike a traditional brainstorm, this type of continuous writing is done in complete sentences and paragraphs.

- Outlining techniques—Allowing students to develop a routine of organizing their thoughts into an outline can help them feel confident when they begin to write. Here’s an example of the Painted Essay outlining model from the Vermont Writing Collaborative.

While there is no one pre-writing strategy I prefer, to set students up for writing success, I do endorse explicitly teaching the pre-writing strategies through the Gradual Release of the Responsibility Model.

The Struggle to Get Set

Teachers must model each part of the writing process, including pre-writing. There is power in explicitly modeling the think aloud, read aloud, and write aloud—students see how it’s done— practice together—before being expected to do it successfully themselves. This practice builds students’ confidence. Teachers must literally show students how to work through outlining a composition before writing it if they expect students to feel comfortable doing this themselves.

After pre-writing, I would teach my students about clustering, webs, thinking maps, and sentence outlining, focusing on determining the question being asked by the prompt. Answering this question would later become the thesis statement supported by topic sentences. Throughout this process, I would think aloud, writing and revising in real time to demonstrate the writer’s cognitive process.

Using a new prompt, I would guide the students, as a class, through the process, clarifying any misconceptions and checking for the students’ comprehension along the way.

After guided practice, the students would be given a new prompt to practice using the process in groups of two. Ideally, I would pair a student proficient in sentence outlining with a student who struggled with the process. And while the students were working in pairs, I would circulate the room, utilizing student discussions to guide my awareness of who was getting it and who needed more support.

Finally, after three direct experiences with pre-writing, students would engage in pre-writing independently using a fourth and final prompt.

The Struggle to Go

In addition to explicitly modeling pre-writing, I recommend that teachers employ customized graphic organizers to support struggling writers.

Graphic organizers illustrate the structure, organization, and relationship between ideas. A well-developed graphic organizer helps focus the cognitive demands of writing for students who struggle. The skills inherent in completing a graphic organizer include skills that target both processing and analyzing.

As a teacher, I customized graphic organizers to target my students’ pre-writing deficits. For example, if a student still struggled with outlining a good conclusion – one of the largest struggle areas – I would find a specific frame for concluding and embed it into that student’s graphic organizer.

Conclusion

Explicitly teaching the pre-writing process and customizing graphic organizers provide a starting point for our student writers. Both of these recommendations take time and planning. I would usually spend two weeks teaching this process for each text type and purpose.

Writing is hard, but so is running. Both are doable. Both are incredibly rewarding.

After running for over a year, completing more than 40 5k races, and clocking more than 400 miles, I still find running hard. But knowing what to do, how to do it, and having clear goals for improvement have made all the difference in my ability to be a successful runner.

After writing for a lifetime, earning a terminal degree, publishing a book, and teaching thousands of students, I still find writing hard. But just as with running, knowing what to do, how to do it, and having clear goals for improvement have made all the difference.

Thank you very much for outlining a model we teachers can use for better preparing our students for the often times difficult yet rewarding task of writing. It makes perfect sense. I hope to help my students make better sense of the writing process as well.

Zack, super read! Thank you for sharing

. . .writing is hard.

Thanks for sharing. I find comfort and validation in your testimony. Blessings to you.

This is spot on, Zack! We teachers need to get over the fear of writing and then show students how to do the same. Our job is to help students get over the fear of a blank sheet of paper! I have a theory. Unwittingly, we have made writing punitive for secondary students; we have managed to suck the fun and creativity out of writing. Teachers know how to assign and grade writing, and we have exhausted a world’s supply of red ink to let students know how poorly they have mastered the art…. But therein lies the problem; writing is an art, and it should be a fascinating exploration of our own minds: what we think, why we think this way, how to explain our thinking, and where we got the fuel to fire our thoughts. Educators need to rethink our grading practices, but “Ahh, that’s where angels fear to tread!”

I feel badly for our teachers, for they are in the crosshairs of administrators, parents, and politicians. They know all about “formative” assessments, but they are expected/required to put a grade in the gradebook five minutes after an assignment is turned in…. The result? We are paying lip-service to what we know is good pedagogy while bowing to the pressure of “traditional grading practices.” Teachers are in a no-win situation. My heart goes out to our educators….

I love your running analogy; we must all put on a new pair of running shoes and get in shape!

This is a great description of effective, simple to implement strategies that are easy to implement. I would add one other strategy – writing fluency practice. When students become more fluent at writing 40-50 words in one minute on their “level”, that blank page becomes much less intimidating. You can find more information here with the ideas from Doug Fisher… https://www.teachingchannel.org/blog/2014/03/31/writing-fluency.

True, writing fluency is critical.

This article is a great resource to use with students and my grandson! I look forward to using the strategy list to help guide me with guiding him to become a stronger writer!