The Great Gatsby, 1984, Little Women, The Picture of Dorian Gray, The Scarlet Letter, Great Expectations, The Things They Carried. Chances are you are familiar with these titles even if you’ve never read the texts. These are just a few books that Goodreads and many others consider to be classic literature. But who decided they would be “classics”? All these titles were books that I was required to read as a student in high school. I couldn’t summarize these texts for you now unless I reread them today. The one exception is The Things They Carried. This book resonated with me because my dad was deployed twice while I was in high school. But that’s just it: I felt connected to this book because of my background and personal experiences. How many educators are choosing novels for their ELA class based on the experiences of their students rather than on a list someone has deemed as required reading?

Yet, it’s not that simple. As an ELA teacher of 4th and 5th graders, I consistently tried to find texts with stories my students could relate to. This meant I had to steer away from the “classics” and research to find authors who built stories around characters who were reflected in my students. This also meant I had to take chances on my students not performing well on specific standards. Common Core Standard RL.4.4 states: Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including those that allude to significant characters found in mythology (e.g., Herculean). The creators of standardized tests are asking students to explain the meaning of words based on texts they assume students have read. The literary device— allusion—appears again in the standard for grade 8, and the standard for grades 11–12 even states to “include Shakespeare as well as other authors.” But I pose the same question: Who are the people making these decisions?

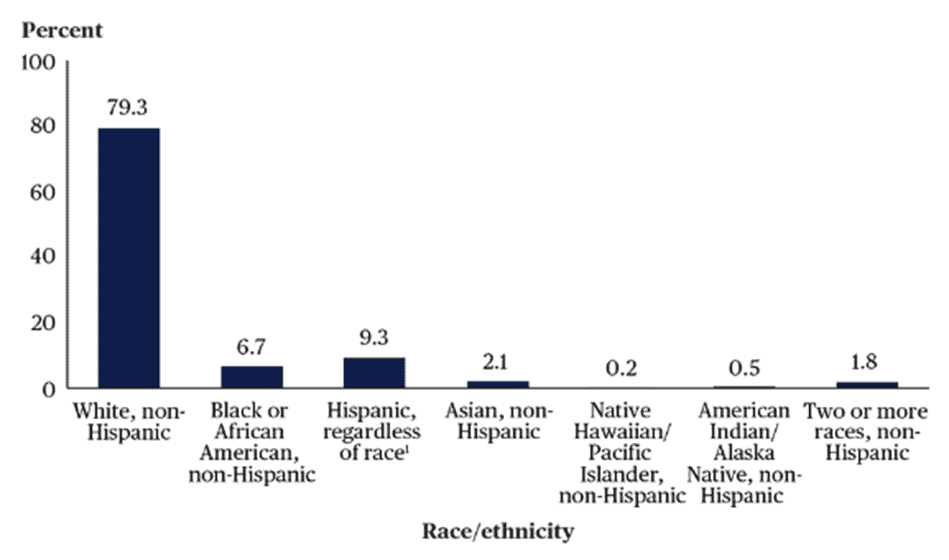

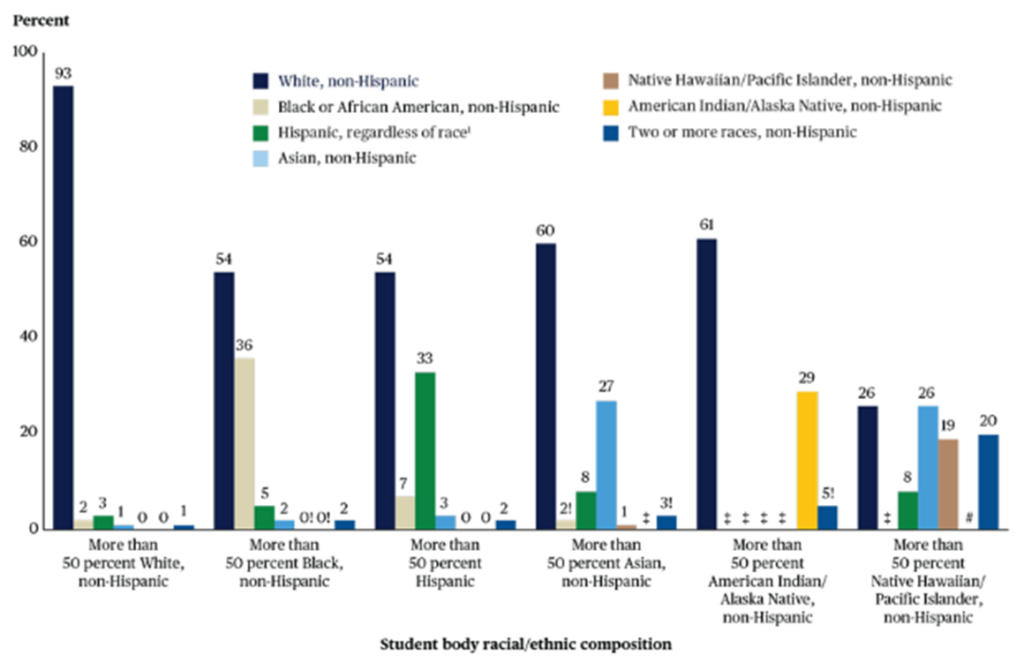

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, the majority of teachers in 2017–2018 were White. Even in schools where the majority of students were non-White, the majority of teachers were usually White. As reported in an article by The Hechinger Report, almost 80 percent of principals in the U.S. are White. With so many educators in the classroom and in leadership roles being White, one might assume that the standards, curriculum, and recommended readings are all being created by White people. Most people enjoy reading stories about people who are similar to them. It’s no wonder that the “classics” mostly have a White character as the protagonist. There are a few “classics” that center around people of color, such as To Kill a Mockingbird and A Raisin in the Sun. Yet, the chosen texts of Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) are often about our pain and suffering. When texts centered around the Civil Rights Movement, the Trail of Tears, or Cesar Chavez are the only stories being told about BIPOC, it creates unconscious biases and paints us as monolithic. And when we ask students to read texts that center around White people and their everyday life, what message are we sending to our BIPOC students? Our classrooms are enhancing and supporting the stereotypes.

NPR quoted a research study in a 2017 article that found students who had teachers who looked like them were more likely to be successful in school. The students in the study expressed feeling like their teachers cared more about them when the teachers looked like them. This led to the students being more diligent in school and setting higher goals. So, what can we do now while we strive to close the racial demographic gap? One thing you can do immediately as an educator is get to know your students. Dig deeper than the cumulative records of a student. Talk to your students at lunch, communicate with parents and guardians to build rapport and remain in constant communication, notice what grabs your students’ attention. Once you have a better understanding of your students, review your curriculum. How many texts are by non-White authors? How many texts center around non-White characters? Is Black History only taught in February? BIPOC students are three-dimensional beings who deserve to have their joy, love, adventures, and lives as the center of stories. Although you may be restricted on curriculum decisions and required to teach specific texts, you can add supplemental materials like videos, interviews, or paired texts that highlight other people and their stories. Finally, do a self-evaluation. Most people assume their personal experiences are shared experiences. Pay attention to the topics you gravitate towards, your word choice, your personal beliefs, and how those can affect you as an educator with students who may not look like you. Take time to do the research and learn the history of different groups of people instead of waiting on others to teach you. Then, the next time you’re planning a lesson to have students memorize lines from The Canterbury Tales, ask yourself: Will my students connect to this? Our job as educators is to reach all students, and we can do that one story at a time.