Through my work with the Council of the Great City Schools, I’ve had the opportunity to visit school districts throughout the country, speaking with leaders and staff at all levels of the system. Often, what we hear in these conversations is a wide range of interpretations of district standards and instructional expectations. What is consistent, however, is that teachers and principals do not feel they have the resources and support they need.

This is one of the reasons we at the Council of Great City Schools have shifted our focus over the last year or so to ensuring that clear guidance and standards-aligned resources are actually making it into classrooms. And we feel that this work begins with the development and implementation of a strong district curriculum. When we look at curriculum documents and guidance materials written by districts, we often see missed opportunities for clarifying the district’s vision and supporting instructional staff.

Our work in urban districts has revealed time and again that, regardless of a district’s approach to instructional management and oversight—whether it is a highly-centralized system or one that places more emphasis on school autonomy—there is a need for this unifying foundation. Learning standards and expectations, for instance, should not vary by school, even if other things do. This provides equity in terms of student learning goals no matter where a student attends school, and no matter how frequently students transfer from school to school. But even when working from the same set of standards, how will staff in every school know whether they have interpreted the curriculum expectations accurately? What would convey the reason they ought to use the curriculum?

What is a Curriculum?

Now, curriculum is a word that means many different things in different places. So this was the first thing we found ourselves grappling with as we were developing our most recent district resource, Supporting Excellence: A Framework for Developing, Implementing, and Sustaining a High-Quality District Curriculum. In this resource, we start by laying out a working definition of a curriculum and the preconditions we feel are needed to ensure that a district’s curriculum has the best chance of improving instruction systemwide.

As far as definitions go, we take a very expansive view of what a curriculum entails. When we talk about curriculum, we are talking about much more than a textbook or a set of instructional materials, and more than a compilation of grade-level college- and career-readiness standards. A district curriculum is the central guide for teachers and all instructional personnel about what is essential to teach and how deeply to teach it throughout the district. It provides guidance for all instructional staff who support and supervise teaching and student learning, and explicitly indicates what the district requires in every classroom, and where schools and teachers have autonomy. And while a curriculum is more than a set of materials, it should identify and connect educators to resources that the district requires, and provide guidance in the selection and use of other classroom resources.

We felt it was essential to get this definition right because, again, when we talk about meaningful support for teachers and classroom instruction, this is where it begins. Districts need to be clear not only about their expectations, but also about the knowledge, skills, and support teachers need to meet these expectations.

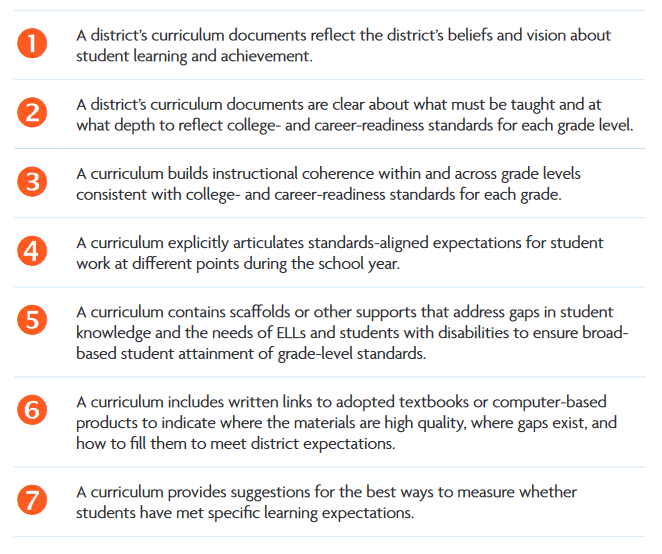

Seven Key Features of a Curriculum

With our foundation in place, we go on to illustrate seven key features of a strong curriculum, providing annotated excerpts from real and simulated district curriculum guidance documents. We know that some districts are developing completely new curriculum documents, while others are revising their existing documents to provide greater support and clarity. These seven features could be the foundation for determining what to include in curriculum guidance. However, a district wanting to revise its curriculum might first take stock of how their curriculum documents address these seven features, and prioritize which ones they need to strengthen given the time and resources they have for curriculum development and the feedback they receive about the usefulness of their current curriculum.

Annotated Examples

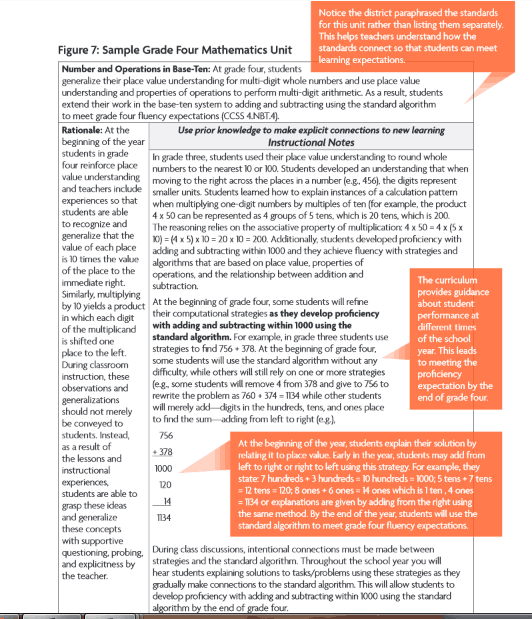

Making our observations and recommendations clear and concrete is one of the biggest challenges we face when we go into districts to conduct reviews and provide support, and it is a challenge we face in developing resources such as the curriculum framework. We hope the examples included in the framework will remove some of the guesswork and frustration curriculum staff face as they work to design and improve on instructional resources for teachers.

It is important to note that, since there is no perfect model for writing curriculum, we use a variety of annotated examples. Some examples even show that multiple features can be incorporated into a model. Each district needs to consider typical student performance and the expertise of its own teaching staff in determining what to emphasize and the level of detail to provide.

It is by design that some of our final recommendations within the framework center on the importance of creating and nurturing strong, two-way lines of communication with teachers and other school-based staff to ensure that a district’s curriculum is providing the types of support and guidance that teachers need. In particular, we encourage districts to:

- Regularly reach out across departments and to teachers and administrators to gauge the quality and alignment of the curriculum and its usefulness to end users in supporting student achievement.

- Establish a process for refining and improving curriculum based on the feedback collected from teachers and administrators as well as student achievement and student work data.

- Clearly communicate all changes to the curriculum to teachers, administrators, and staff, acknowledging the role of data and feedback in these revisions.

This framework will support districts in designing curriculum with both the instructional vision of the district and the needs of teachers in mind; implementing it district-wide in a comprehensive, inclusive manner, and continuing to refine and improve it based on feedback from the front lines is what makes it a “curriculum” and not just a textbook series or a set of learning standards. That’s the difference between sending out boxes of materials and providing teachers and administrators with meaningful guidance and the support they need to best serve students.