Early in my career, when beginning a research project or debate, I’d roll out my trusty lists of pro/con topics and wait for eager researchers to dive in. Abortion! School censorship! Gay marriage! Instead of students diving in, though, they could barely be coaxed to wade. Some would quickly choose a topic and proceed to “research” by cherry-picking quotes that supported their predetermined position. Others would stare listlessly at the topics and brand them all “boring.”

I thought my lists were providing choices, that topics “ripped from the headlines” were enough to stimulate curiosity. They aren’t. So many of our students have so little context of what’s happening in the world around them that these topics are totally out of reach for them. They’d likely be curious about many of them…if they knew what we were talking about. Years of trial and error have finally shown me students are better able to explore complex topics when we slow down and use a variety of texts to build curiosity.

Step One: Choose a broad theme and find out what they know.

The first step is choosing a theme to guide your students’ thinking. In my AP Seminar class, one dedicated to research, I like to keep my themes broad when I’m trying to activate student interest. Currently, we are in the midst of a unit called Monsters. Our guiding question is simple: What do monsters look like in our world?

We begin each unit with low-stakes writing. My students maintain blogs for class, so to open the unit, they blog about their answer to the unit question. I learn what they know and what they want to know. With the monster unit, I discovered many see figurative monsters in our world: drugs, stress, suicide, sexual assault, and terrorism. What they understood about those topics varied greatly, but it gave me a an idea of which issues would be most likely to spark some interest. I also learned that many were interested in literal monsters–Bigfoot, the Lochness Monster, El Chupacabra–and it made me wonder if those students might be interested in researching different cultures and how we tell stories.

The key to this step is listening to your students and being willing to choose your teaching materials based on what they tell you.

Step Two: Explore texts from many genres.

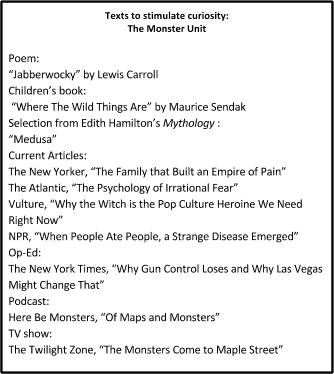

The next step requires a little digging on the part of the teacher. I pull texts from as many genres I can find. This isn’t researching yet, so non-research-y texts (poetry, podcasts, op-eds, etc.) might stimulate questions in a way that dense articles may not.

As we read and view the separate pieces, we continually return to our unit question. Before and after every class discussion, I ask students to make some notes about the texts we’re discussing in their notebooks.

Before: What are your initial ideas about this text? What questions does it raise for you?

After: What did others say that sparked new questions for you? What do you think now that you hadn’t considered before our discussion?

My text choices are always very loosely strung together with the common thread of the unit theme and attempt to address questions from student blogs, but they are purposely very different from one another. My goal is to expose the students to topics they hadn’t considered in the hopes that I will spark questions they didn’t know they had.

Step Three: Generate questions

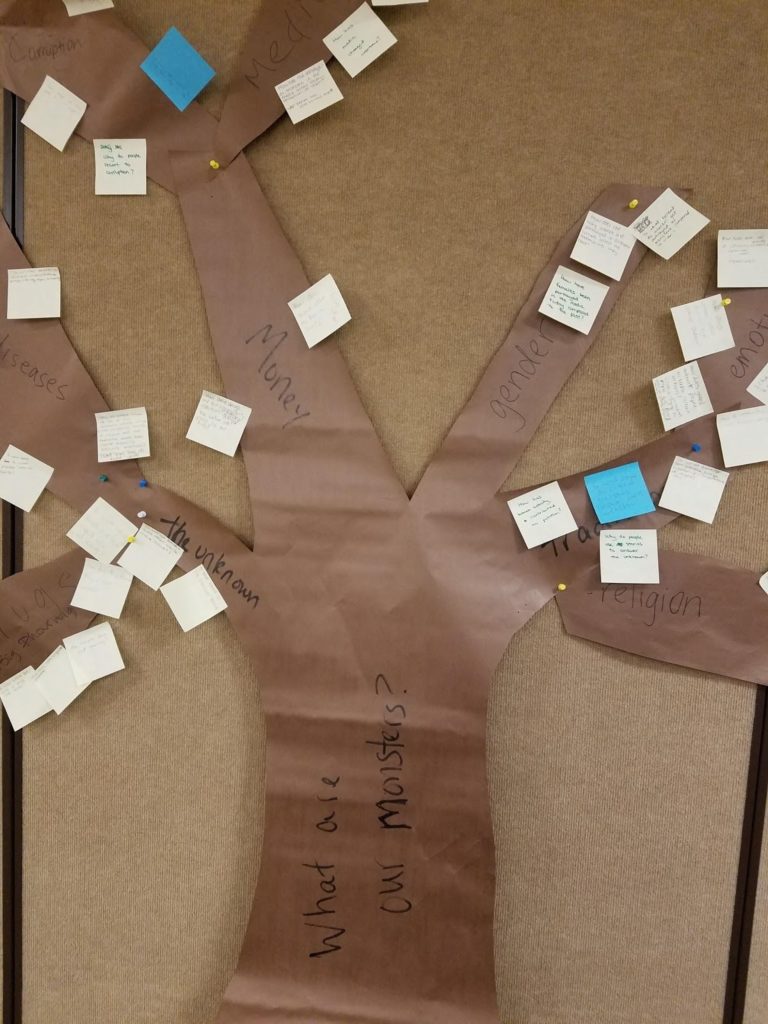

After a week of reading and viewing the texts as separate pieces, we take a day to return to those notes from each individual text discussion and use them to start looking for ways to group the topics.

For example, students saw in this unit a connection between the poem “Jabberwocky”–full of nonsense words that “sounded” scary–and the article about irrational fear. It prompted some questions about how language differences create fear and distrust. Another student was curious to know more about how profit drives different industries. The questions and the discussions of them sparked others. By the end of the day, they were ready for another blog entry, this time to further explore a potential question. Those blog posts will guide one-on-one teacher/student conferences the following week as students finally dive into their research.

Years ago, I would have cringed at the thought of wasting time puttering around in different topics. I know now, though, that it’s not a waste at all. Investing the time up front and building curiosity naturally pays off once the research begins. We have created something for them to dive into together, and I no longer have to coax them at all.