I’m a teacher leading Professional Learning Communities (PLCs) for many novice teachers who were not trained in the science of how children learn to read. What can I do to help them understand what foundational skills instruction should look like?

I’m a coach working with a team of principals who have done in-depth work on the use of complex text. The trouble is, they look for it in every classroom, on every desk, at all times. How can I help them make sense of the value of decodable texts in the early grades?

How much time should we allot for the teaching of foundational skills?

As an ELA/Literacy Specialist who has spent the past twenty months or so digging deeply into the world of foundational skills and emergent reading, I often receive questions like the ones above from fellow educators doing similar work.

Scientists and reading researchers are in agreement that the most effective way to teach the “how” of reading is through systematic instruction in phonological awareness, phonemic awareness, phonics, and fluency. At first glance, the act of teaching a four-, five-, or six-year-old to read an early reader with basic words and sentence structure appears deceptively simple. In reality, the nuance of early reading is exceptionally complicated. Unlocking the speech sounds of language, and teaching young children to associate those sounds with the letters on the page, is some of the most specialized teaching there is. The associated terminology alone—phonemes, graphemes, digraphs, rime—can give you a sense of how much there is to know to be an effective teacher of early reading.

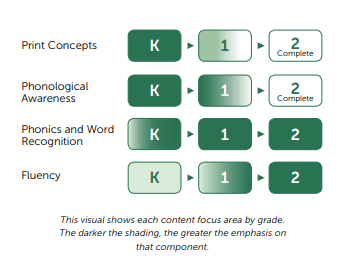

The Components of Foundational Skills:

And yet, practitioners are not all on the same page in terms of what to do or how to do it (see Emily Hanford’s recent report on this subject for American Public Media to better understand the challenges faced here). There is a great deal of variation found in the field about how to teach these crucial areas of early literacy, with discrepancies based on whether or not the school, district, curriculum, or training the educators had was based in this research. This means that a school’s approach to foundational skills instruction is often entirely up to the teacher, school, or district’s individual decision making, leading to avoidable challenges.

So what guidance can we offer? How can we help clear up the muddied waters that prevent teachers, school leaders, and other educators from being on the proverbial same page?

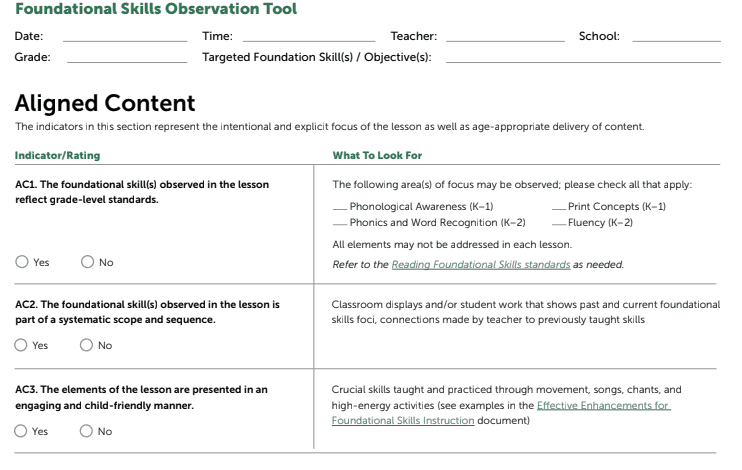

That’s the question we set out to answer in designing our new Foundational Skills Observation Tool. Designed with the same goals as our anchor Instructional Practice Guides for ELA/literacy and mathematics, this tool is meant to support content-specific observation and feedback that allows for the teacher and the observer to be on the same page about what constitutes best practice for foundational skills instruction in kindergarten, first, and second grade. The tool is designed to provide concrete guidance at the observable indicator level, answering the question: What does effective foundational skills instruction look like in the classroom? By offering observable indicators in four categories (Aligned Content, Teacher-Directed Instruction, Student Practice, and Assessment & Differentiation), this tool provides a common language to use when observing and giving feedback.

| Category | Indicators on the Observation Tool |

| Aligned Content | The intentional and explicit focus of the lesson, as well as age-appropriate delivery of content. |

| Teacher-Directed Instruction | The teacher-driven moves in the lesson, such as what the teacher says, models, and assigns. |

| Student Practice | What students say and do throughout the lesson. This format may change throughout and can include whole group, small group, independent, and teacher-supported tasks/practice. |

| Assessment & Differentiation | Strategic collecting of data as well as adjustments to instruction based on observed student need. |

Why is this important?

According to Richard Elmore, “content-specific feedback is a critical part of a teacher’s professional development. The highest-impact feedback and professional learning are framed in the context of the student-teacher-content interactions of the instructional core” (Elmore, 2000). Given the inconsistency of teacher and school leader training with a focus on foundational skills, it is more important that staff across the board have a common vision of what teacher practice looks like, and a tool that allows teachers to be supported and coached, whether by a supervisor, coach, or peer.

Necessary but not sufficient.

An observation tool is not a substitute for training, support, and high-quality instructional materials. Common language without the resources needed to act will fall flat. We highly encourage educators, and those who work with them, to immerse themselves in foundational skills training and to utilize high-quality instructional materials that support these best practices. With this combination, teachers can develop their skills and respond to actionable feedback to address the needs of the students learning to read in their care.