As the chair of the math department at my high school, I am always looking for ways to support our teachers and students. Whether I’m sharing an instructional strategy or a new pedagogical point of view, my goal is always to work collaboratively with teachers for our shared purpose: supporting our students. Last year, I found myself constantly questioning if the way I assessed and graded students accurately reflected their level of proficiency, and if the feedback I provided was enough to help them improve. I wondered if teachers in my department felt similarly. It turns out they did, and these uncertainties (and our desire to feel more confident in our instruction) are what led my content team to standards-based teaching.

Making the transition from traditional grading to standards-based teaching and grading was exciting and intimidating because I did not know where to start or how to go about it but I knew it was necessary. In this blog post, I’ll discuss the inspiration behind the change, an example of what the changeover looked like, and our implementation of standards-based feedback.

Inspiration

After attending several conferences centered on collaborative common assessments, I was introduced to the book Standards-Based Learning in Action. This book was exactly what my team needed to make our switch. The book is designed to guide teachers on breaking down the current traditional grading practices happening in the classroom, why they aren’t working, and why standards-based teaching and learning will support instruction better. Throughout the reading, I reflected on how I could shift my teaching and grading practices to best serve the needs of my students.

The four core principles that the team took away from the book were: 1) separating behavioral factors from the academic grade, 2) how to create formative and summative assessments, 3) how to give feedback, and 4) how to actively use feedback for student improvement. Personally, I found the feedback chapter–and using it for student improvement–to be the most empowering areas of reading and the most exciting to implement.

Changeover

Let’s take a look at the core principle of separating behavioral factors from the academic grades. As an example, if a student turned in an assignment late, I used to give him/her half credit. Why? It was the norm I learned when I started teaching. However, what if the work was completely accurate and the only problem was punctuality? Should a student’s grade be affected? No. The timeliness of work submission is what requires attention–as well as solutions to such an issue–not the grade. This falls under behavioral characteristics, or separating the academics from behavior. With standards-based teaching and grading we can focus on the three important factors: standard(s) proficiency, behavior, and academic growth. This focus results in what all teachers want: students performing to their best abilities.

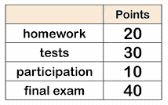

Now that we’ve  seen a separation of academic and behavioral grading, let’s look at how to create academic growth with standards-based feedback. With grades, how many of us can relate to using the percentage breakdown shown in the graph on the left or something similar? I know I used to. But where in these four categories do we capture the skill(s)/standard(s) where students need support? Truthfully, we can’t do that with this breakdown model. This picture does not give an adequate breakdown of students’ a

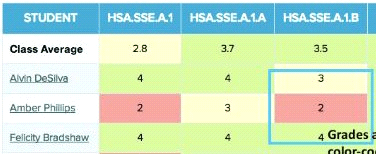

seen a separation of academic and behavioral grading, let’s look at how to create academic growth with standards-based feedback. With grades, how many of us can relate to using the percentage breakdown shown in the graph on the left or something similar? I know I used to. But where in these four categories do we capture the skill(s)/standard(s) where students need support? Truthfully, we can’t do that with this breakdown model. This picture does not give an adequate breakdown of students’ a cademic performance on the standards and mastery of them. With standards-based reflection, you get a clear snapshot of students’ strengths and areas for growth within the standards. Looking at the graph on the right, it is evident if the student is weak in one standard but stronger in a related standard, giving me an area to focus on for remediations.

cademic performance on the standards and mastery of them. With standards-based reflection, you get a clear snapshot of students’ strengths and areas for growth within the standards. Looking at the graph on the right, it is evident if the student is weak in one standard but stronger in a related standard, giving me an area to focus on for remediations.

Initial Implementation

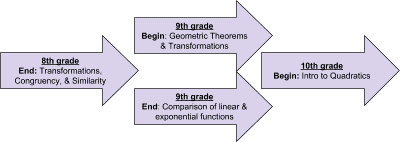

Over the course of time, our team, with administration support, actively moved through implementing the core principles. Our transition had its challenges, from finding the time to do the work to learning how to collaborate frequently on creating collaborative common assessments. Our first action step was to rearrange our curriculum modules so as to align with the last unit from eighth grade and end with a transitional unit into Integrated Math II, as shown by the diagram above. This alignment helps students see the connections between the transition of the math content from middle school to high school. For teachers, it helps them visually see the cohesiveness of the standards within the modules for all three grade levels. Our next action step focused on selecting essential standards necessary for Integrated Math 1 based on the vertical articulation of our standards between Integrated Math 1 through Integrated Math II. Finally, our third step centered on the development of each unit and how to give the best first instruction.

creating collaborative common assessments. Our first action step was to rearrange our curriculum modules so as to align with the last unit from eighth grade and end with a transitional unit into Integrated Math II, as shown by the diagram above. This alignment helps students see the connections between the transition of the math content from middle school to high school. For teachers, it helps them visually see the cohesiveness of the standards within the modules for all three grade levels. Our next action step focused on selecting essential standards necessary for Integrated Math 1 based on the vertical articulation of our standards between Integrated Math 1 through Integrated Math II. Finally, our third step centered on the development of each unit and how to give the best first instruction.

In conclusion, although this transition may sound tedious and/or time consuming (at times it may be), think of it as “you have to go slow to go fast.” So when asking, “Why the change to standards-based grading?” Consider if what you are doing is not working and leaving you dissatisfied. If so, then why not?

Would the content of the book be for literacy standard alignment for grades 1-5?