This article originally appeared on the Mr. G Mpls Blog. It has been reproduced here with permission from the author.

The “knowledge-gap” is pinpointed most recently by Natalie Wexler as a culprit for continued stagnant reading proficiency levels and growing disparities in student outcomes in the U.S. Thankfully, more and more are realizing that students’ ability to think critically and creatively is severely hampered without a solid foundation of background knowledge.

Yet beyond adopting a “knowledge-rich” curricula and understanding the importance of building a deep structure of knowledge, I’ve recently caught myself struggling to think of how, specifically, knowledge-building happens within lessons. As in, I was unsure exactly how a knowledge-rich curriculum was brought to life and best imparted to students on a day-to-day basis.

While I prioritize class time around a cohesive curricula with reading, writing, and discussion and have found tremendous benefits from using knowledge organizers, I was still left feeling my approach to “knowledge-building” was missing…something. That something, I learned recently, was robust vocabulary instruction.

Why Is Vocabulary Important?

As a profession, we’ve come to associate a variety of stale and ineffective practices with vocabulary instruction. I used to practice the following “vocabulary activities,” deliriously hoping I was building students’ vocabulary.

- Repetitively teaching vocabulary with the same definition (this is actually rote learning)

- Using matching exercises and one-dimensional puzzles

- Having students copy opaque, poorly-written definitions from dictionaries or glossaries

- Challenging students to vaguely “write a new sentence using this word.”

What I and many others have passed off as vocabulary instruction is completely inadequate and fails to allow students the opportunity to take advantage of the power of a deep and interconnected vocabulary. Shanahan (2005) writes in The National Reading Panel Report: Practical Advice for Teachers.

“The importance of vocabulary is beyond doubt…such knowledge is integral to any activities that involve language, and psychologists have shown how vocabulary is more than a list of ‘word meanings in the mind,’ but actually functions as an index of a much richer and harder to measure constellation of understandings and experiences.”

This interconnected web of vocabulary we each carry around has been found to be a vital foundation for reading comprehension. In Bringing Words to Life: Robust Vocabulary Instruction, Beck, McKeown, and Kucan (2013) highlight the close relationship between vocabulary and reading comprehension.

“There is much evidence – strong correlations, several causal studies, as well as rich theoretical orientations – that shows that vocabulary is tightly related to reading comprehension across the age span.”

And so, while the empirical support for vocabulary instruction is present, what are teachers to do with more than a quarter million words in most dictionaries? How can teachers best approach the daunting, yet crucial challenge of vocabulary instruction? To start, the answer is certainly not to rely on independent reading to do the job.

Beck, McKeown, and Kucan (2013) point out that while “wide reading” is indeed an important source of vocabulary development for students, it should not be seen as a replacement for robust instruction.

“Written context is clearly an important source of new vocabulary for any reader. But relying on learning word meanings from independent reading is not an adequate way to deal with students’ vocabulary development.”

Furthermore, the Matthew Effect must be considered. Shanahan (2005) points out “studies suggest lower achieving readers acquire less incidental vocabulary than good readers acquire.” In other words, it is teachers’ great responsibility to provide all students with access to the vocabulary required to experience success in school. First though, we have to figure out what vocabulary to teach.

Three Tier Framework

The Three Tier framework, articulated by Beck, McKeown, and Kucan (2013), is a powerful tool to help teachers categorize and identify high-value vocabulary that can improve students’ verbal functioning and reading comprehension. Essentially, words are categorized into three buckets:

- Tier One: “Words typically found in oral language.” These words are typically found in high frequency word lists, and do not require much focus as students hear these on a regular basis in conversation.

- Tier Three: “Words that tend to be limited to specific domains.” These are the words textbooks typically put in bold. While important, these words have limited use outside the specific content area, and are not very helpful for enriching descriptions or explanations.

- Tier Two: “Words that are more characteristic of written language, and not so common in conversation.” These are words that students will not hear, but will encounter across various domains as they read and write in school. These words are to be prioritized for instruction.

It’s estimated that to read with minimal disturbance in comprehension, readers need a vocabulary of around 15,000 words. Of those 15,000 words, Beck, McKeown, and Kucan (2013) conclude that 8,000 are Tier One which require minimal focus, and 7,000 are Tier Two and should be the focus of robust vocabulary instruction. That breaks down to between 300-400 Tier Two words per year to be deliberately taught alongside the context/content they authentically arise.

Tier Two words are so important because they fundamentally expand students’ verbal functioning by building rich representations of words that can be used in a variety of contexts. These Tier Two words empower students to provide more specific, mature ways of describing and explaining the world. While an exact science does not exist to pinpoint Tier Two vocabulary, Beck, McKeown, and Kucan (2013) do provide some helpful questions to ponder when identifying Tier 2 words.

- Generally, how useful is the word; will students see it in multiple contexts; will it help students better describe their experiences?

- How does the word contribute to the overall text being read; does it communicate vital meaning or tone?

- How does the word relate to other words and previously-learned content?

Having identified a rough process identifying Tier Two vocabulary, what are best practices for introducing, teaching, and assessing this vocabulary?

Best Practices for Teaching Vocabulary

When designing vocabulary instruction, it is important to keep in mind two words: frequency and robustness. Beck, McKeown, and Kucan (2013) write about the importance of providing “frequent and varied encounters with target words and robust instructional activities that engage students in deep processing.”

To accomplish frequent and robust encounters with vocabulary, the instructional sequence for words is spread across at least three days, but ideally five or more days. In this sequence, a variety of deliberately-designed exercises are done with students to use the words to describe new contexts, explore the multidimensional nature of words, and consider relationships among words (seriously, buy the book, it is loaded with exercises to use!). Here is an outline of the instructional sequence recommended in Bringing Words to Life:

- Day 1: Introduce words to students with student-friendly explanations and context

- Days 2-4: Follow-up activities

- Identify examples/non-examples; form word associations with new contexts, additional writing exercises (The Writing Revolution makes for a great supplement here).

- Day 5: Assessment

When introducing new vocabulary, Beck, McKeown, and Kucan (2013) highlight the importance of providing student-friendly explanations, the original context the word came from, and opportunities for students to interact with word meanings. “A robust approach to vocabulary involves directly explaining the meanings of words along with thought-provoking, playful, and interactive follow-up.”

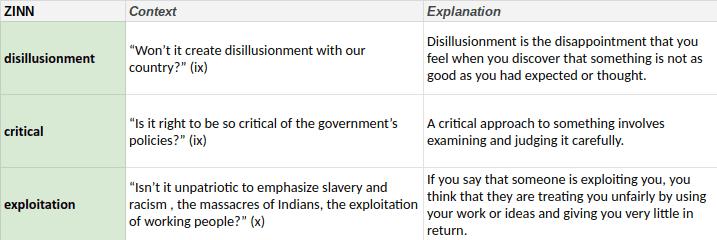

Therefore, to get started, I first scanned each lesson’s text for Tier Two vocabulary, and then created a table with the target word, instructional context, and a student-friendly definition modified from learner’s dictionaries. (Optional: I also created a “student dictionary” with the explanation cells left blank for students to fill in as a lesson starter).

Then, I created a variety of exercises (example/non-example and writing sentence stems) to be completed with students to start lessons after the new words have been introduced.

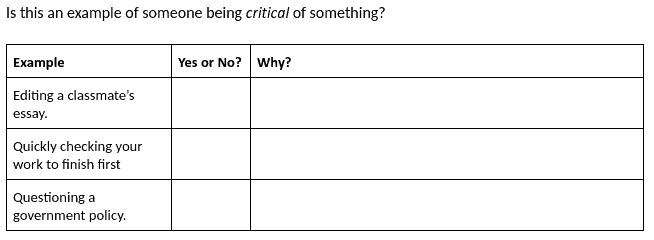

Ideally students are working with each word 3-4 days in a row, and further challenge should be gradually added by having students generate new situations to match target words (e.g. How would a critical person write about a music show?). Here’s an example of encouraging students to interact with vocabulary meaning in new contexts.

The key is to make sure students are having plenty of opportunities to explain why they made the yes/no choice they did, and then to discuss it whole-class. While students complete this table, they have their “student dictionary” available to refer to.

Finally, at the end of units, I created true/false assessments with explanations to measure more surface level knowledge (e.g. does a critical person think carefully before making decisions?) and deeper knowledge (e.g. how can the history of Columbus be analyzed critically?). In this way, the full instructional sequence of Tier Two word instruction is designed to simultaneously improve students’ verbal functioning and activate background knowledge.

Summary

Robust vocabulary instruction is a crucial driver of knowledge-building. While many knowledge-rich curricula might emphasize the importance of vocabulary and identify key vocabulary words in each lesson (typically Tier Three), ultimately the quality and robustness of vocabulary instruction comes down to teacher expertise and judgement.

Shanahan (2005) summarizes it best: “the most effective direct instruction in vocabulary helps children gain deep understanding of word meanings (much more than simple dictionary definitions); requires plenty of reading, writing, talking, and listening; emphasizes the interconnections among words and word meanings and the connections of words to children’s own experiences; and provides abundant ongoing review and repetition.”

We do a disservice to students when we devalue vocabulary instruction to a level of copying definitions and matching exercises. Knowledge-building is made more robust with vocabulary instruction.

I’m on Twitter.

References

Beck, I. L., McKeown, M. G., & Kucan, L. (2013). Bringing words to life: Robust vocabulary instruction. Guilford Press.

Shanahan, T. (2005). The National Reading Panel Report. Practical Advice for Teachers. Learning Point Associates/North Central Regional Educational Laboratory (NCREL).

This is a great research-based post on effective vocabulary instruction! I’m a big fan of BRINGING WORDS TO LIFE, and I’ve developed some additional tools that readers might be interested in here: https://theliteracycookbook.wordpress.com/2018/08/08/techniques-and-tools-for-vocabulary-instruction/

This sounds great. I would love to have a copy of this information

Is there a book that has your ideas for teaching vocabulary. Of there is please email me the information. Thank you