This blog post focuses on moves teachers can make to build students’ knowledge of the world. For more on this topic, see our free, three-part mini-course on Building Knowledge

My 8-year-old daughter plays soccer, and like many working parents I often have to miss her practice. I’ll ask her about it later that evening and she’ll tell me how many goals she scored during the scrimmage, or if someone else on the team did something particularly noteworthy. She has good coaches—I know they are teaching her real stuff, like how to kick from the inside and outside of both feet, and how to up the number of passes the team makes, but she never shares those specific points. She talks about soccer; she likes the game.

I’m a literacy specialist, and I promise for those less invested in sports, that this is a metaphor for reading instruction!

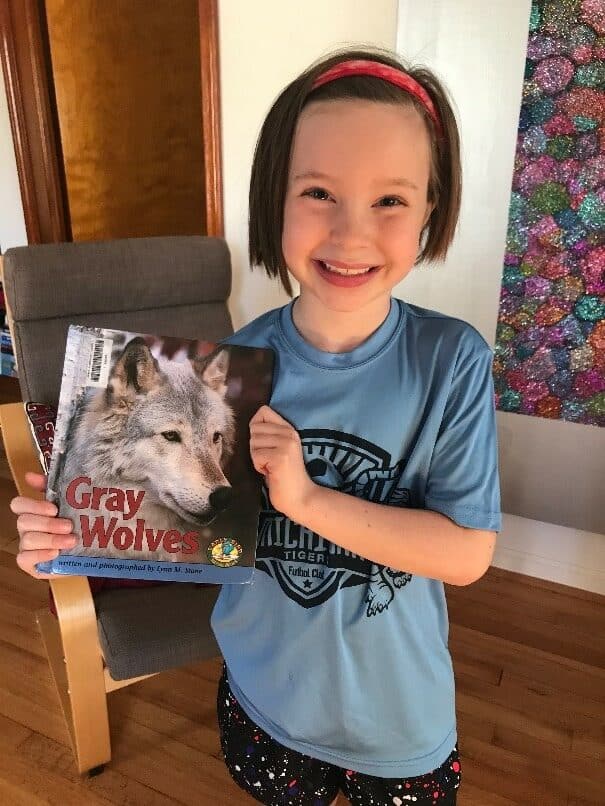

This same child met me at my home office door at the end of the day recently, eyes shining, a book clutched in her hand. “Mom!” she cried, “We’re doing something really cool now in school!”

I’d love to claim this moment as a reflection of my successful parenting, but I’ll be honest here and say that my daughter’s typical depiction of a day of learning is, with painful prompting, typically limited to something along the lines of “we had art today.” But on this day, there was real news: the “cool” something she was referencing was an actual research project on an animal of their choosing. (She chose wolves.)

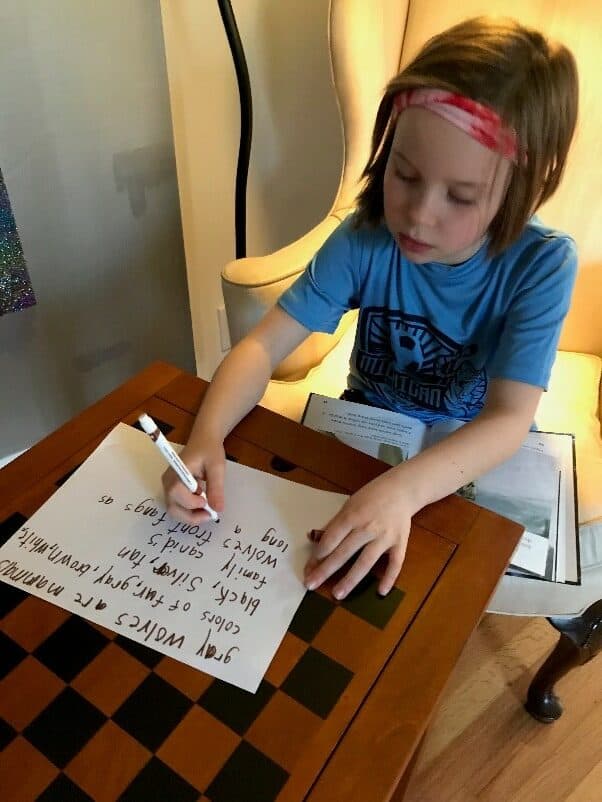

The project itself doesn’t seem particularly noteworthy—there were library books involved, a report, and some sort of poster. In second grade “standards language,” she was doing a mix of shared research and writing, gathering information from provided sources, and perhaps even comparing and contrasting information across texts. But the spark of joy in her eyes as she told me about the project and the enthusiasm she showed toward the work–see the completely not-staged before and after soccer practice pictures below for proof: as soon as soccer was over, she immediately returned to her task!–was entirely about a love of learning new stuff.

|

|

When families are chatting with their children on the trip home from school or after-care, at dinner, or while getting tucked in at night, their conversations likely sound something like one of the conversations described above. Children share things they love, things that strike their interest, or nothing at all! And yet, in literacy instruction, we often lose the forest for the trees by focusing on evidence of learning, like identifying a main character, and losing the learning itself.

College- and career-ready standards point to an increased focus on building knowledge through content rich nonfiction. This increased focus was needed for a range or reasons. Back in 2000, researcher Nell Duke found a mean of 3.6 minutes a day of informational text reading was happening across 20 first grade classrooms—practically nothing! And yet, in a study called The Baseball Study, researchers Donna Recht and Lauren Leslie showed that students’ knowledge of a topic they are reading about—baseball in this case—has almost as large of an impact on student performance as generalized reading ability does. Students who were able to connect what they were reading to their own background knowledge (and, likely, lived experiences) were successful in comprehension tasks beyond what they might have been able to do if reading about unfamiliar content. Contrary to the idea that students have one reading level, we can make the assumption here that reading levels vary based on the readers’ knowledge of the topic.

There are many ways to look at this information—the takeaway is not about every student learning about baseball. In actuality, knowledge of baseball served as a scaffold for students who had relevant experience with the topic, allowing them to access text that may have been out of reach otherwise. Far too often in reading classrooms, attention is spent on disconnected elements of literacy instruction like specific skills and strategies, and not on intentionally building or supporting all students’ knowledge of the world. Students are regularly asked to predict, summarize, or infer without focusing on the goal of understanding a text and gaining knowledge from it. With this model of instruction, students often rely on what they do or don’t already know about the topic of their reading.

However, we know that the knowledge found in texts does not always match the rich funds of knowledge all students bring with them to the classroom—and this is often especially true for students of color and/or English Learners. The narrow skills-based approach limits all students, but it’s especially harmful to those who are not seeing their lives, language, and experiences reflected in text.

This can be alleviated in multiple ways: by committing to knowledge-rich content through text and making use of text that connects to the lives, experiences, and funds of knowledge of all students. Truly equitable instruction will level the playing field by both utilizing diverse texts that speak to the lived experience of all students and building the new content knowledge and vocabulary necessary to develop grade-level reading skills and talk or write about what they’ve learned. And from the children’s perspective: they’ll just know reading is what enables them to learn about wolves.

There is no reason literacy work needs to happen in a vacuum, and there are many ways in which we as educators can connect to the funds of knowledge students walk in the door with and build new knowledge by exploring rich content with them at school. My daughter happened upon wolves in her project, but if rich and varied content was explored through literacy units across the course of her school year, she’d build knowledge and vocabulary related to new topics throughout her academic career. The result of this work would be a wealth of new words she understood, facts she could discuss, analyze, or write about with nuance, and a clearer sense of what she loved or disliked about what she was learning. At the very least, a far more interesting dinner table conversation.

To get started bolstering knowledge in your classroom, read this blog on text sets, explore Achieve the Core’s text set collection, and learn more about strategic organization of your classroom library through book baskets. Looking to make a bigger change? Consider a literacy program focused on knowledge-building such as the free, open-access Core Knowledge Language Arts, EL Education, and Match Fishtank.