This post is the third in a series of blogs addressing culturally relevant pedagogy, and how we can move towards culturally relevant practices using standards-aligned instructional materials as a starting point. Student Achievement Partners recently partnered with a group of educators to explore using the Historically Responsive Literacy (HRL) framework, defined by Dr. Gholdy Muhammad in her book, Cultivating Genius: An Equity Framework for Culturally and Historically Responsive Literacy. The resulting prototypes address the four pursuits of the HRL framework (identity development, skill development, intellectual development, and criticality) applied to various curricula. In this blog post, two of the project’s designers, Adrienne Williams and Alexis Mays-Fields, share their insights.

Where did the initial spark for this project come from?

Adrienne: Can you remember a time when you were in school when you felt completely and unconditionally supported, championed, and cultivated? A favorite teacher, a life-changing text, the project that shifted how you saw the world and yourself? Those moments are what I’ve always believed school should be for all students, but I know that is not often what school is for most students, particularly Black and Brown students.

In her book, Gholdy Muhammad defines genius in students as “the brilliance, intellect, ability, cleverness, and artistry that have been flowing through their minds and spirits across generations.” This expression of what students innately possess resonated with me and others so much that it served as a call to action to figure out how we could bring that experience to students in the schools and classrooms we serve. We knew a big part of that work would be focused on what was put in front of students in the first place: the curriculum.

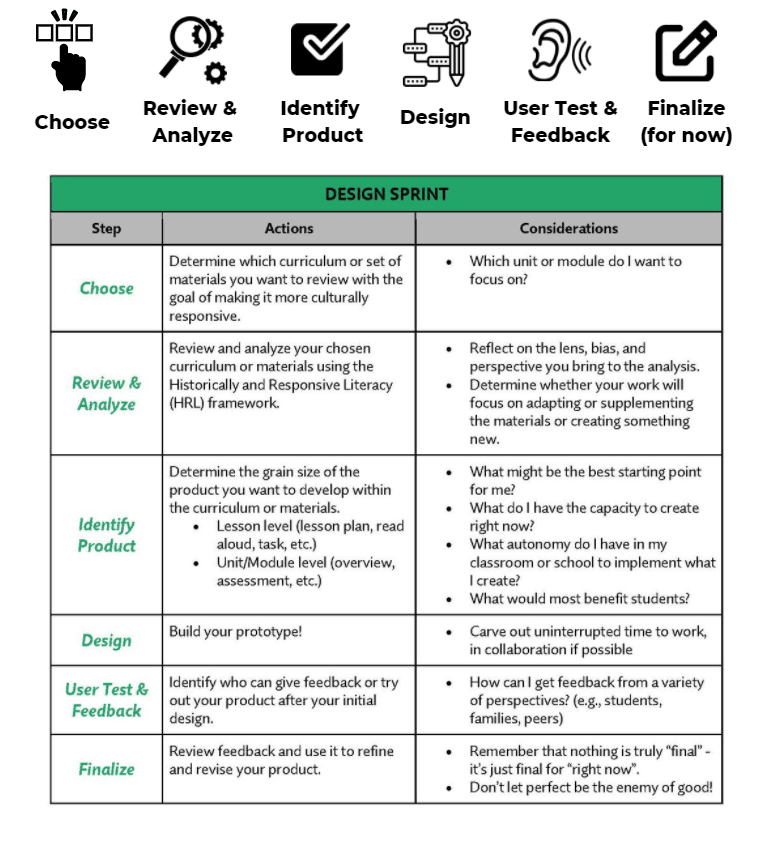

In my experience teaching CKLA and supporting implementation of the EL Education curriculum, it was clear to me that the chosen texts, the historical narratives that were being perpetuated, and the voices and stories that were missing could not be ignored. We put together a pretty simple design sprint to help us explore and adapt materials.

What was the process?

Our team’s design sprint centered the four learning goals or “pursuits” of the Historically Responsive Literacy framework, described by Dr. Muhammad below:

- Identity development; defining self; making sense of one’s values and beliefs;

- Skill development; developing proficiencies through reading and writing meaningful content;

- Intellectual development; gaining knowledge and becoming smarter;

- Criticality; developing the ability to read texts to understand power, authority, and oppression.

Alexis: Each week we met to work our way through the sprint. As we broke into our smaller groups, it was always clear that we were working with a group of educators who had such a passion for this work. The Zoom rooms were filled with conversations about how we could flip curriculum upside down using the HRL framework. It was the best possible way to nerd out!

What did you learn?

Alexis: So, what did we learn that we didn’t already know? I believe I speak for many of my colleagues during this process when I say we were able to confirm that the curriculum that many of us are using do not include the voices of Black and Brown students. We have the power to uplift Black and Brown voices in the curriculum that already exists because now we have the tools. The HRL framework ignited a fire within each of us and gave us permission to dismantle, rework, and revive learning in such a way that speaks to underserved identities. It is also my strong belief that through this process we learned how to cultivate instruction in a way that not only says, “Black or Brown child, we see you,” but we now have a framework that can be used across grade levels and subjects.

Beyond unmasking the framework to yield better outcomes for students, this experience also helped us unmask the vulnerability within ourselves. Each Zoom session unearthed stories about our own identities and struggles within education. It was during those sessions that we realized there were times when we were victims; there were teachers who helped us see ourselves for who we truly were, and then there were those moments when we had to apologize for being the teacher who failed to honor the worth of the children of color in our classrooms. By listening and sharing with each other, we received the feedback necessary to challenge the status quo. We were in a safe place to be unapologetically diverse and radical if we wanted to, all in the name of shifting the instructional landscape for students. There were many nights of reflection and soapbox antics that always helped us work our way into crafting the perfect show pieces for the world.

Adrienne: I learned that this takes a lot of time! Time that teachers don’t often have to dig into their materials and learn them deeply to begin with, let alone to consider changing or adapting them. That means it’s important for leaders to consider how to make time for teachers to learn about the HRL framework, their curriculum, and their students. You also need to be open and willing to learn about yourself.

The second big takeaway for me was that while many of the curricula we worked with are touted as “high-quality,” there are still big gaps in identity and criticality. Teachers need the space to be able to adjust and supplement their materials to address these really important components but often do not have that autonomy. If you’re starting this work, it’s important to ask yourself: Where’s my entry point? What is in the locus of my control? Where can I take risks or find support to do something different?

“Final” Products

Here you will find prototypes and sample templates used during this process. We want to name that these are still prototypes. They are worth continuous improvement as we try them out in different spaces and get more feedback. We invite you to take a look, try them out, and make them your own. We’d love to hear from you about what you’re trying!

A Call to Action

Gholdy Muhummad writes, “I argue throughout this book that we need more than small movement or change in education, but transformation. And transformation has to be collaborative. This level of change does not happen if our universities, schools (and leadership), and communities are not working toward this progress (pg 169).”

And so the question becomes, how will you cultivate genius? During our time together, we often asked ourselves how we could bring this work back into our school networks, communities, and classrooms. We decided that, with the wealth of gems that we received, we would be willing to fight—one lesson at a time, one unit at a time, and one curriculum at a time.

It is true that this work isn’t easy, but it is worth it. This work isn’t always received well, but there are students in your classrooms who will thank you for seeing them as they authentically are. This work can be lonely, but it doesn’t have to be. There are educators within your building, your city, and your community who are having these conversations. Find a thought partner and start where you are.

Works Cited:

Muhammad, G. (2020). Cultivating genius: an equity framework for culturally and historically responsive literacy. Scholastic, p. 13.

Would like to see additional resources please.