As we’ve been highlighting in this series, Student Achievement Partners has helped to play a role in defining many elements of literacy instruction for the last 10 years. And for a long part of our organization’s history, that meant talking about Shifts of the Common Core. The Shifts were, quite honestly, a huge part of why I was so excited to join the team at SAP 8 years ago. Because like my colleagues and so many teachers, I too was sold stories about what it means to teach literacy, and the Shifts played an important role in how I learned to do better.

Like many young educators, I entered the classroom through an alternative route program. And as a middle school teacher, the stories I was sold weren’t about early reading and foundational skills but rather about how we engage kids with texts. In my training program, I was taught that teaching reading to middle schoolers was simple. The standards outline reading skills, so my job was to break them down and then teach the skills to my kids. And if my kids couldn’t apply the skills with texts that were at grade level, then I was to just give them a text they could read to use to practice the skills. The idea was that the skills we practiced would transfer from one text to another, and eventually, kids would be able to apply those skills to more and more challenging texts.

What did that mean in my classroom? Well, I started the year by giving an assessment to determine my students’ reading levels. Then, I used that data to direct my students to book bins that matched their Lexile level and had them choose “just right” books to use to practice the standards. From there, we were off, spending time each week learning about the skills defined in the standards: finding the main idea, looking at sequences of events, identifying cause and effect relationships; the list went on. After a brief mini-lesson, I would send the students to their independent reading books and ask them to practice whatever skill we were working on that week in their leveled text.

In theory, anyway. In practice, I found myself constantly reteaching, spending weeks and sometimes months at a time on a specific standard, never seeing the “growth” my mentors assured me was coming. What’s more, I could tell that my students were bored. The kids who had needs related to decoding weren’t getting practice or support with the skills they needed to develop. And they hated being placed into “baby” books. They would often ask how they could possibly do things like “compare characters” when their text had only one. Their needs were, quite simply, not met by the instruction I was providing.

Meanwhile, my kids who were on level or exceeding often got tripped up on complex vocabulary words or challenging syntax, and I never had the time I wanted to dive deeply into this with them because everyone was reading something different. I was constantly trying to track progress and measure goals, with more individually leveled books than I could possibly keep up with in a single class period. And the progress I hoped to see never came; that first year, the gaps in my classroom only increased as time went on.

That first year of teaching is one I’ve reflected back upon often, but it wasn’t until later in my teaching career, when I learned about the Shifts, that I was able to put a finger on why that first year was such a failure on my part. Through the literacy Shifts, I finally saw how I wasn’t designing instruction around the needs my students truly had.

We weren’t building knowledge by deeply engaging with complex texts, nor were we using evidence from texts to support our ideas in writing and speaking. When I learned about the Shifts and the practices that supported their implementation, so many things about why that first year didn’t work for my students fell into place. I became a Shifts superfan and eventually joined the team at SAP to help spread the message of shifting practice to better support students.

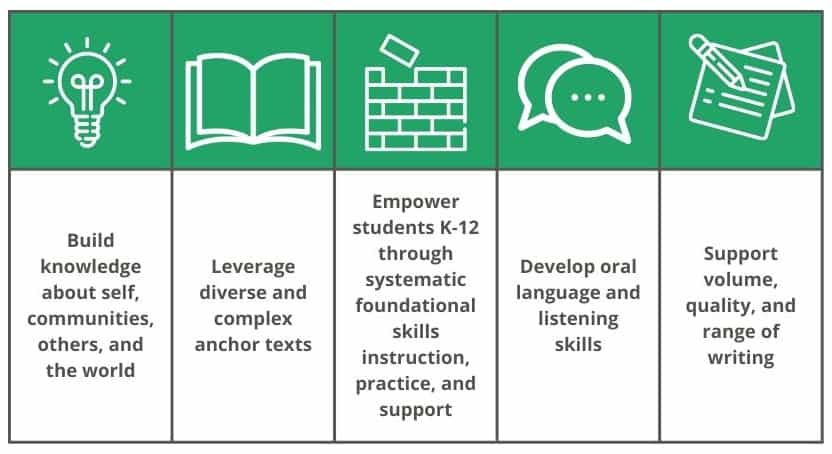

Since working at SAP, I’ve been grateful for how our organization has evolved in our thinking. Because while the Shifts provided me, and other teachers like me, a better way to do things, they still were too narrowly focused. Lots of essential ideas were left out of the Shifts. For example, when we talked about complex texts but used example texts with primarily white authors, we created a false dichotomy between complex and diverse texts that negatively impacts students in classrooms right now. And when we talked about building knowledge absent conversations about what and whose knowledge we were talking about, we ignored important conversations about the impact of race and power in classrooms. To be clear, I still do believe in the importance of Shifts as one piece of the story of equitable literacy. But I believe in a version that is more complex and nuanced than where we started, and the fact is that I need to tell more complex and nuanced stories in my work supporting educators. We can talk about what knowledge we build, and how we leverage diverse and complex anchor texts to do it. We can talk about systematic foundational skills beyond grade 5, and we can talk about developing oracy and writing skills:

It’s my hope that as we at SAP continue our learning, we also continue to weave together more complete stories about literacy to support educators in the hard work of leading classrooms.