The two previous posts in this series have introduced the characteristics of reading fluency and identified strategies for building fluency, but how do you determine the type of fluency intervention your students need? Some of your students may already be reading texts at their grade level fluently, while others may be struggling with texts several years below grade level. As you think about the level of intervention necessary and determine which Fluency Packet will meet the needs of different students, you can use these strategies for assessing fluency and identifying where students are struggling.

First, it’s necessary to regularly assess students to ensure they’re developing the fluent reading skills necessary to support comprehension as texts become more difficult across grades. Being a fluent reader with narrative text in third grade does not ensure the reader will be fluent several years later. Developing adequate reading fluency is a growth process that must be monitored as students progress across grades.

A full assessment of reading fluency includes consideration of the three indicators – accuracy, pacing, and prosody. Accuracy and pacing can be combined into one metric called accumaticity which represents the total number of words read correctly during the assessment (the total number of words read minus those that were misread, omitted, or inserted, often called WCPM or CWPM).

Accumaticity: We introduce the term accumaticity to refer to the quantitative measure reflecting the number of words read correctly in one minute. This avoids an incorrect reference to WCPM/CWPM as “fluency”, which it is not. A common practice in the past has been to refer to WCPM/CWPM as “fluency.” However, this is incorrect because the metric does not reflect the indicator of prosody. As such, we introduce the term accumaticity to recognize this important difference and reserve the use of the term fluency to include all three indicators of fluent reading.

Outlined below is a process for assessing fluency development. For those who exhibit unambiguously fluent reading when they are assessed, the assessment stops. For readers who display less than adequate reading fluency, a second level of assessment is recommended.

The fluency assessment process can be accomplished by listening to a student read a grade-level passage aloud for a brief period of time while monitoring the three indicators of fluent reading. Reading must be assessed with texts that have been measured for appropriate quantitative and qualitative difficulty within the recommended CCSS grade-level Lexile bands. Below are links to the two best respected and widely used evaluation systems with some explanations about how they work:

Hasbrouck and Tindall Norms

http://www.readingrockets.org/article/fluency-norms-chart

http://www.readingrockets.org/content/pdfs/Hasbrouck-Tindal_chart.pdf

Rasinski Prosody Rubric

http://www.timrasinski.com/presentations/multidimensional_fluency_rubric_4_factors.pdf

When we assess reading fluency we must keep in mind a model of what good readers do when they read a text. For example, they pronounce all the words correctly and, in cases where they don’t, they quickly correct their own mispronunciations. Good readers neither skip words nor do they insert words into the text. Competent readers do not replace a word in the text with a similar word in meaning or one which is similar in appearance (for example, reading “when” for “where”). Finally, good readers use an appropriate pace and read with prosody.

Our recommended protocol for fluency assessment is as follows:

- Find a quiet location where the student can be easily heard while reading aloud. Explain to the student that you wish to find out about their reading, that it’s a regular part of the teaching process and is not done for a grade.

- Have the student read the text aloud using the student version of the passage while the teacher uses the administrator version.

- Before assessing the student, gather these required materials:

- A timing device.

- A copy of the grade-level passage from which the student will read.

- A scoring version of the same passage used by the person giving the assessment.

- Before beginning the assessment, instruct the student to read the text in their normal reading voice and tell them that once they’ve finished you will ask them a few questions about what they read.

- To begin assessing, instruct the student to start reading aloud when you say “begin” while you simultaneously start the timing device from “0” seconds.

- As the student begins reading, monitor word accuracy, pacing, and prosody. This process will be familiar to teachers who have used informal reading inventories or who have conducted running records.

A note of caution: Other fluency assessment tools are fine as long as they use texts that have been 1) appropriately leveled by grade using quantitative and qualitative tools and methods recommended in the supplement to Appendix A of the CCSS, and, 2) include the three indicators of fluent reading – accuracy, pacing, and prosody. Because many assessments ignore the indicator of prosody, an incomplete and even misleading picture of fluency may emerge. Also, many informal assessments will recommend texts for specific grade levels using older and lower complexity levels often resulting in overstated fluency ability. The assessment should also include a test of comprehension.

- Accuracy: While the student is reading, you identify reading “miscues” as they occur. For words that are mispronounced or not read (omitted or skipped), simply cross them out. Do not attempt to record the mispronunciation as this may cause subsequent miscues to be missed. If necessary, a phonics assessment can better address the nature of miscues (this is discussed later). For words that are not part of the text but are inserted into the text by the reader, place a “carrot” (^) where the reader adds the word to note the word insertion. When the student self-corrects a mispronunciation, do not count this as a miscue. The goal is to use a simple system of noting reading miscues so that one mark equals one miscue. When the reader has finished, record the total number of miscues by counting your marks.

- Pacing: At the end of 2 minutes, insert a mark after the last word read (whether read correctly or not). If the reader finishes before 2 minutes, record the total seconds that it took to read the passage (e.g., 1 minute 43 seconds equals 103 seconds).

- Prosody: To assess reading prosody, use a modified version of a rubric designed by Zutell and Rasinski (1991). While the student is reading, listen for the 4 categories of fluent reading – 1) Expression/Volume, 2) Phrasing, 3) Smoothness, and 4) Pace. When the student is finished reading, score each of the 4 categories as 1, 2, 3, or 4, then sum the four numbers to arrive at a single score between 4 and 16. Study the prosody rubric before assessment begins. Recording the student on a laptop device as they read is helpful as the recording can be carefully evaluated once assessment is finished. Note – The scoring of prosody requires some practice on the part of the evaluator. However, the time spent acquiring this skill is greatly rewarded through a deep understanding of fluent reading!

- Comprehension: Once the student is finished reading, ask the student each of the comprehension questions and record their answer as correct or not. Correctly answering the comprehension questions in the accompanying passages reflects minimal understanding of the text and is not meant to be an assessment of deep understanding. It is important to include these questions for two reasons: 1) Students who read fluently but struggle with correctly answering these basic questions require a deeper understanding of their difficulty and 2) Students might read a passage differently if they know there are not questions or tasks at the end.

Scoring Each Reading Passage:

Scores for accuracy, pacing, prosody, and comprehension will be obtained for the assessed passage. Two of those scores, accuracy and pacing, can be combined into accumaticity as follows:

- Count the total number of words read (whether read correctly or not) by referring to the mark made to indicate the last word read at the expiration of 2 minutes, or if the student finished the passage in less than 2 minutes, the total number of words in the passage.

- Count the total number of reading miscues.

- Subtract the miscues from the total number of words read to arrive at the number of words read correctly (WRC).

- Record the total number of seconds it took the student to read the passage (120 for 2-minutes or total seconds if less than 2-minutes)

- Divide the WRC from step 3 by the Total Seconds in step 4 and then multiply by 60. The result is accumaticity, the number of correct-words-per-minute (CWPM) for the passage.

Accumaticity combines accuracy and pace (2 of the 3 fluency indictors) into one measure. However, this does not yet reflect fluency because we have not considered prosody, the third indicator. - To interpret accumaticity (CWPM), it must be compared to a “norm.” (i.e. a number representing a national average). Using the Hasbrouck and Tindal (2006) norm chart compare the CWPM for your reader to the norm reflecting the grade-level and time of year during which the assessment was administered (fall, winter, spring).

- Prosody: Now rate the student on the prosody rubric by assigning a 1, 2, 3, or 4 for expression and volume, phrasing, smoothness, and pace. Sum the four scores to arrive at an overall prosody score between 4 and 16.

- Finally, total the number of comprehension questions answered correctly.

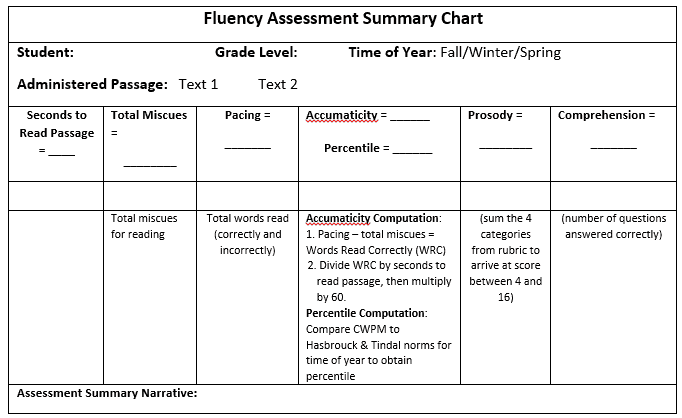

The following table (also attached in a Word document) will be helpful in organizing your assessment summary:

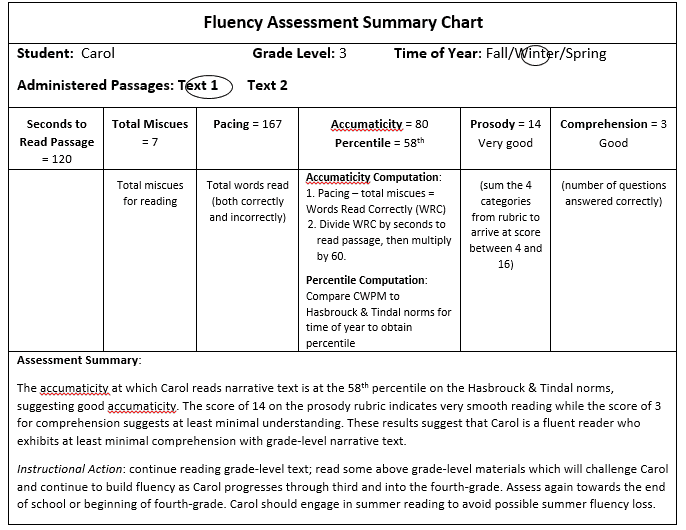

An Assessment Example:

A third-grade narrative text passage is administered to Carol, a third-grade student, in the winter of the school year. In two minutes, Carol reads 167 words with 7 miscues. The WRC (words-read-correctly) equals 160 (167-7). The teacher then divides 160 by 120 (convert 2 minutes into seconds) to arrive at 1.33, and then multiplies by 60 to arrive at an accumaticity score (or CWPM) of 80 (round off to the nearest whole number). Grading of the Prosody Rubric for Carol’s reading of the narrative passage is done by assigning a score (1, 2, 3, or 4) to each of the four categories (expression/volume = 4, phrasing = 3, smoothness = 4, and pacing = 3), and then adding them to arrive at a score of 14. Of the three comprehension questions, Carol correctly answered three.

The accumaticity score (CWPM) of 80 can now be compared to the Hasbrouck and Tindal (2006) reading norms for narrative text. A good goal is for students to be no more than 10% below the accumaticity score for the 50th percentile. The normative chart shows that for third-grade readers in the fall, a score of 71 equates to the 50th percentile. A minimum score would be 10% below 71 or about 64 (71-7 = 64). Carol scored an 80, well above the 50th percentile (about the 58th), suggesting she reads with appropriate accumaticity.

The score of 14 from the Prosody Rubric suggests Carol reads with appropriate prosody. On the comprehension text Carol scored a 3, suggesting at least minimal comprehension of the passage. These scores have been inserted into the Fluency Assessment Scoring Chart below. Notice that at the bottom of the chart there is an assessment summary for each of the two text types.

Interpreting Fluency Assessment Results

The objective of assessing reading fluency is to first, distinguish those students who are most likely fluent readers from those who are not. Maintaining appropriate fluency is challenging as texts increase in complexity from grade to grade and it’s important to screen all students to ensure that proper fluency growth is occurring. While not all readers will find the texts in the next grade challenging, some will. For example, it can be assumed that students who score “Distinguished” or in the highest category on the end-of-year state assessment read with appropriate fluency and do not require an assessment. For students who scored “Proficient” on the exam, an interpretation should be made as to whether they made a score near the bottom end of the range. If so, the teacher may consider assessing their fluency. Students scoring at the “Novice,” “Apprentice,” or lowest two ranges in the state test should absolutely have their fluency assessed.

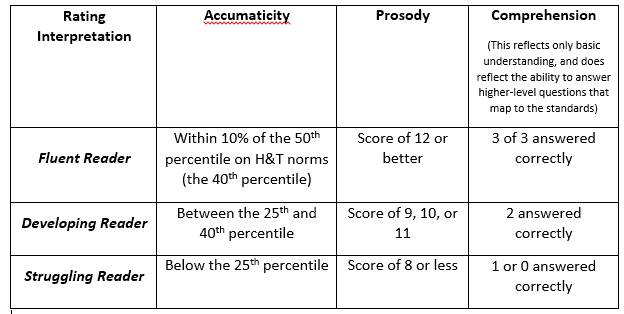

After a fluency assessment is completed, how does the teacher identify those who are most likely fluent from those who are not? The interpretation chart below will help with this.

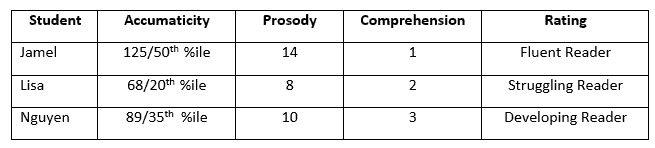

Let’s consider three readers, Jamel, Lisa, and Nguyen, who were assessed for fluent reading. Their scores are in the table below.

Jamel: This student reads fluently but appears to struggle with comprehension. Remember earlier when we said that fluency does not guarantee comprehension? However, it’s too soon to say that Jamel comprehends poorly. It would be good practice to administer Jamel some additional comprehension assessments or refer to other assessments that your school may have administered such as the MAP, DRA, or the end-of-year state assessment. For example, have him read a text and give an oral retelling. See how Jamel comprehends text where he has some knowledge of the subject matter, versus text he knows little about. Find out if Jamel does fine with factual questions, but struggles with questions focused on inferencing and hypothesizing. The point being, while Jamel reads with good fluency, his comprehension processing needs more investigation.

Lisa: With an accumaticity score at the 20th percentile and a prosody score of 8, Lisa struggles with reading fluency. A next step with Lisa would be to administer a test that can provide insight into her decoding difficulties. If decoding is an issue, then instruction to fill in her phonics knowledge would be beneficial. While Lisa does show some degree of comprehension processing, it may be useful to confirm her ability with other assessments. It would be an instructional mistake to ignore Lisa’s fluency challenges and focus only on comprehension, as unlike Jamel, Lisa has significant fluency challenges which are very likely affecting her comprehension ability.

Nguyen: This student does exhibit some fluency ability that with further investigation and instruction may be quickly improved. A test of decoding ability (recommendations are below) should be administered to Nguyen to determine the extent to which he understands decoding and is or isn’t automatic with words. It may be that Nguyen is a competent decoder, but because of minimal practice, has yet to become a fluent reader. Nguyen’s comprehension score of 3 suggests adequate basic comprehension.

Comment on ESL Students: One might suspect that one or more of these students may be an English-language learner. If this were indeed the case then our fluency reading assessment must be tempered with knowledge of the student’s competency with English. For example, Jamel might be an ESL student who has mastered fluent reading, but because of a lack of depth and breadth in vocabulary and knowledge, his comprehension is challenged. If Lisa were an ESL student, her fluency scores might reflect tremendous progress and learning if she had only recent exposure to English. At the same time, her fluency with reading English can be expected to be developing while she is learning English. Nguyen may come from a family of first-generation immigrants who hears very little English at home. At the same time, he may have been in the U.S. for several years, all of them while attending school. If a decoding assessment suggests that his phonics knowledge is strong, increasing reading fluency may well be a matter of more practice with texts at his instructional level and above. Some of this instruction may require teacher scaffolding or assisted reading. Remember, it’s important to explore the background of ESL students to determine their specific language and cultural situation, and then factor it into a determination of their reading ability and subsequent instruction.

Digging Deeper – The Role of Phonics

Students who have been assessed for fluency and identified as struggling readers are in need of further evaluation to determine the nature of the problem. A place to begin is to administer an assessment to determine what they know about phonics and whether or not additional instruction in this area may be helpful.

There are many assessments which can help determine the source of a student’s phonics difficulties. One such assessment is the Scholastic Core Phonics Survey assessment available on-line at the link below. Other assessments include the Diagnostic Reading Assessment-2 (DRA-2).

CORE Phonics Survey (available for use in this link)

The authors provide specific guidelines to determine a student’s current reading fluency level, and, further, pinpoint problems impeding students from becoming fluent readers. In two previous posts, characteristics of reading fluency and, identified strategies for building fluency were introduced.

Strategies are offered for assessing fluency and identifying where students are struggling.Regular assessment is provided to assess: accuracy; pacing; and, prosody. Further, recommendations are offered regarding respected and widely used evaluation systems,e.g., Hasbrouck and Tindall and Rasinski’s Prosody Rubric. The authors recommend a six step protocol for fluency assessment. Again,, a note of caution is provided when assessment of comprehension is being made with regard to: accuracy, pacing, and prosody.

Further, additional recommendations (8 steps) are provided for scoring and interpretation of for each passage (see the Fluency Assessment Summary Chart) to determine if the reader i: (a) fluent; (b) developing,(c) struggling).

Finally, recommendations are offered to address findings when students are identified as struggling readers

Although this assessment doesn’t measure reading comprehension, if we ask students basic comprehension questions following a students’ disfluent reading, we can’t in fact determine anything about comprehension. In reviewing Rasinkski’s fluency assessment protocol, he takes a different approach. He recommends that upon the student completing their 1 minute timed reading, the teacher re-reads the entire passage aloud to the student and then asks comprehension questions. What is the rationale for the adjustment in the protocol above?

Great question. This is really a matter of purpose. If your goal is to assess comprehension of a grade level text, regardless of student reading fluency, the Rasinski approach you are recommending is effective. Another effective practice would be comprehension questions after a read aloud, with attention to individual student responses in writing or discussion. The protocol here is meant to zoom in on a student’s fluency and it’s connection to comprehension. This both messages to the student that the purpose of reading is meaning making and supports the teacher in identifying where meaning making breaks down.

Carols’s assessment results are what I see the most of in my role. Students that are fluent readers however still struggle with comprehension. In these cases we are told to obviously continue with grade level texts and even high level texts. In my school population I see students that struggle with content as opposed to fluency. This is difficult to get to the bottom of because many of our students don’t have the experiences to understand such complex texts. In this case I do a lot of front loading and discussion about the text.

It was interesting to read about how one determines the fluency intervention our students may need. Some may already be reading texts on grade level fluently while others may be struggling with texts below grade level. Regular assessing is necessary to determine their current reading skills. Reading fluency would include 3 indicators as mentioned in other modules: accuracy, pacing and prosody. Accuracy & pacing can be combined and called accumaticity. This measures the number of words read correctly in one minute. Fluency would be evident if they are pronouncing the words correctly and self correcting when necessary. Also, not skipping or inserting words would be demonstrated. Accuracy is demonstrated along with comprehension.

Many students I have worked with are like Jamel. Many of these students struggled in reading comprehension. Many of these students have been able to have reading fluency but lack of the comprehension. In many cases, the lack of prior knowledge of the text, or the lack of certain vocabulary impede the full comprehension of the text. That’s why the selection of the text it is so important and the exposure of all kind of text.

As a teacher you should assess students frequently to see where their needs are and therefore plan accordingly. As a PEP teacher it is very important to choose a quiet area without distractions when assessing my students. This gives me a more accurate picture of where my students are in their learning.

The reading assessments results are interesting. When I taught kindergarten I had a lot of students who scored higher on fluency than comprehension.