“What kinds of things do you want to read next year, Amelia?”

Amelia, one of my reading intervention students, looked down at the assessment passage we’d just read. It was a short biography of 17th-century naturalist, Maria Sybilla Merian.

“I want to read more like this,” she said, pointing at the passage.

That brief conversation inspired the planning for a unit I would teach to Amelia’s group the following school year, a unit in which I worked to integrate everything I knew about both my students and the research about strong reading instruction.

I’m an old timer in the science-of-reading game, having been interested in research since 2005. It was around this time that the national Reading First initiative came to my school, and the conversation about reading instruction became fraught. Right now, we’re experiencing another such period, thanks in large part to the buzz around Emily Hanford’s Sold A Story podcast. Often, this conversation is portrayed as a “war” pitting those who advocate for science against those who believe in responding to students as individuals.

So where does that leave those of us who are trying to put all this into practice for students like Amelia?

Over the years, I’ve outlined a few principles to help me plan in ways that take into account research into reading instruction, as well as the needs of my individual students: readers in grades 3–5 who need extra support. These principles include:

Using assessment to identify instructional focus.

I use data from a range of formal and informal sources to identify student needs and form groups. I use this data to discuss with students their individual areas of focus. I also regularly interview students about their interests and feelings about reading.

Planning units to build knowledge and vocabulary.

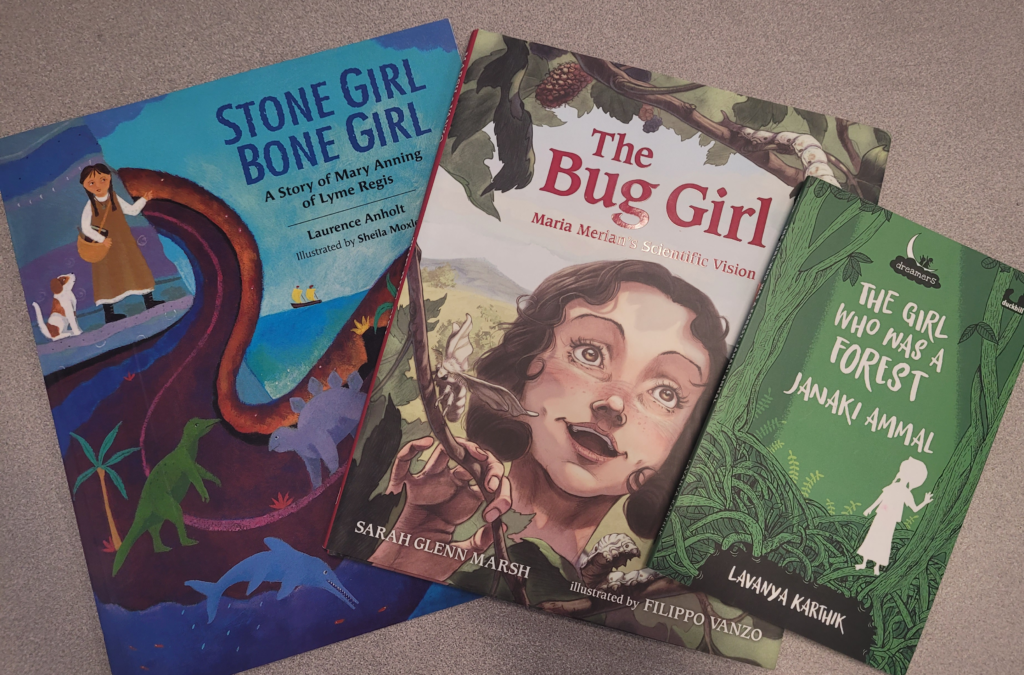

Research tells us that knowledge— of both concepts and words—is critical for reading comprehension. For this reason, I plan instructional units based on text sets with conceptual links. For the unit inspired by Amelia’s interest in Maria Sybilla Merian, I selected texts about two other naturalists, Mary Anning and Janaki Ammal. All three texts emphasized the importance of careful observation in science, the challenges of women finding a space in the sciences, and the vocabulary of various scientific fields.

When selecting texts, keeping in mind complexity, engagement, and diverse representation.

There has long been the belief that students need texts at their “just right” level—books they can read with approximately 95% accuracy. However, more recent research has shown that students may progress even more with scaffolded, challenging texts. And if that’s true, it’s a matter of equity to select texts that will challenge students to deeper thinking. It’s also important to reflect the world around us and engage students in thinking critically about how diverse perspectives are represented. As I planned this unit on historical naturalists, I realized that the first two texts I’d selected were about European women. I wanted to ensure that our unit not only pushed against stereotypes of gender in the sciences, but also against the idea that science is exclusively the province of Europeans and their descendents. This led me to the text about Indian botanist Janaki Ammal.

Planning scaffolds to support your specific students’ needs.

When teaching with challenging texts, scaffolds must be carefully chosen based on students’ needs. I spend the bulk of my planning time reading and analyzing the texts I will teach, asking myself: Which words, phrases, or sentences will be difficult to understand? What will be familiar to students? What scaffolds might address barriers to understanding? When I can answer these questions, I plan our reading to put these scaffolds in place. For example, we may review specific phonics concepts, learn critical vocabulary, or explore historical background.

Using research-based instructional routines.

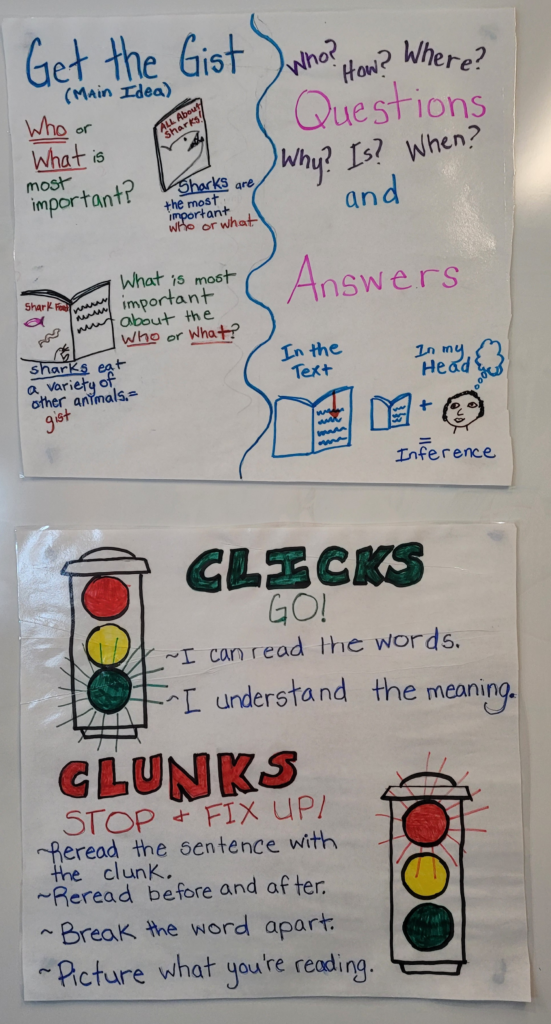

There are many instructional routines developed and tested by researchers, such as Reciprocal Teaching, Concept-Oriented Reading Instruction (CORI), and Collaborative Strategic Reading (CSR—educators love a good acronym!). I use CSR with my students, which provides a framework for before, during, and after reading. By using a routine, students know what to expect from each lesson, and they can direct cognitive effort toward reading and understanding the text.

Research-based instruction doesn’t have to be about following a scripted program or a focus on phonics alone. By defining principles grounded in evidence, and getting to know students’ needs and strengths, we can plan well-rounded instruction that engages both the hearts and minds of our students.

Thank you for this insight. I especially appreciate you pointing out the need for planning scaffolds based on student needs.

I completely agree with your views and I appreciate your approach. As a reading intervention teacher, you encouraged me to go ahead and push my groups to read more challenging texts with my support.

Sarah! That’s great to hear! Please reach out if you have questions or want support. I’m @EvidentlyR on Twitter.

Great article and important to raise the issue of cultural responsiveness in choosing texts, as well as the importance of scaffolding challenging texts. I’d add that thematic text sets gives students the opportunity to encounter and use similar academic vocabulary and concepts throughout a unit, thus giving them a higher chance of integrating them into their linguistic and conceptual repertoires. This is especially important for English learners and for students who hadn’t the chance to be read to as regularly prior to coming to school.