Teaching students how to approach personalized word-learning is one of the greatest ways that we can empower them as readers and learners. However, teachers, unsure of the best approach to improving reading skills and vocabulary knowledge, often rely on word memorization from word lists.

Most career- and college-ready standards address the strategies involved in word-learning. The standards (with grade-level variations, of course) ask students to be able to use word parts and patterns, context clues, and outside resources to aid them in learning words from reading.

However, it was not until a few years ago that I realized that these three strategies are not ones to use randomly or in piecemeal fashions. They are actually a sequence that helps students use word-solving skills efficiently and effectively.

When students approach unfamiliar words in a text, they should:

- Look for morphological clues (inside word clues)

- Look for context clues (outside word clues)

- Consult an outside resource (outside text help)

Many educators wonder why we should have students look for morphological clues (roots, prefixes, and suffixes) first since many assessments measure vocabulary knowledge with context clue questions. Simply put, the most efficient and effective strategy for determining a word’s meaning is comparing its parts to other words we know. McCormick and Zutell (2011, p. 308) state, “Context assists with confirming the meaning of a word, but it does not replace the need to use letter and sound knowledge.” So, in other words, although context clues are an important strategy, morphological knowledge in most cases is more efficient. In fact, context clues only help students identify unknown words in a passage about 20% to 35% of the time (McCormick & Zutell, 2011)!

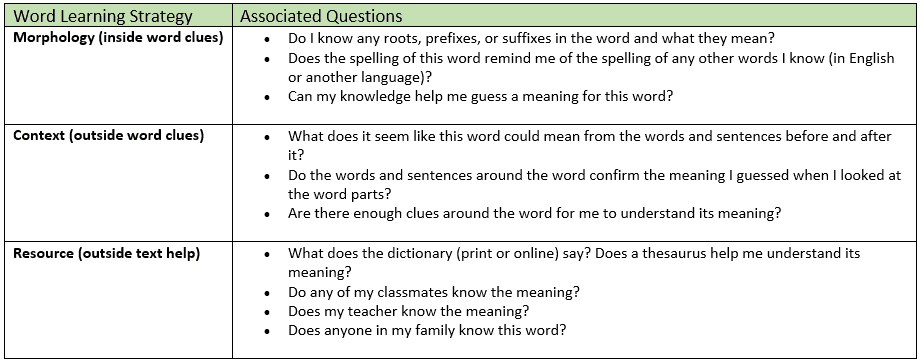

We can teach students the metacognitive skills to approach unfamiliar words by having them ask themselves a sequence of questions as they read. I have included a helpful handout that can be used as a classroom poster or a reference for students.

1. Morphology (inside word clues)

- Do I know any roots, prefixes, or suffixes in the word and what they mean?

- Does the spelling of this word remind me of the spelling of any other words I know (in English or another language)?

- Can my knowledge help me guess a meaning for this word? If the answer is no, or you are not sure, move to step 2.

2. Context (outside word clues)

- What does it seem like this word could mean from the words and sentences before and after it?

- Do the words and sentences around the word confirm the meaning I guessed when I looked at the word parts?

- Are there enough clues around the word for me to understand its meaning? If the answer is no, or you are not sure, move on to step 3.

3. Resource (outside text help)

- What does the dictionary (print or online) say? Does a thesaurus help me understand its meaning?

- Do any of my classmates know the meaning?

- Does my teacher know the meaning?

- Does anyone in my family know this word?

For many students (especially striving readers), consciously enacting this process may be difficult because it seems unfamiliar to them. Many will skip over words or search for context (that may not always be there). That’s why I find two approaches help students begin to think in this way. First, teacher modeling of this self-questioning through think-alouds as the class reads a complex text begins to have students see how the strategy works. Also, students can work in pairs to identify unfamiliar words and coach one another through the process like an interview. I linked a separate handout that asks students to practice this with one another. (Note: the differences are subtle.)

Metacognitive strategies for word-learning must be scaffolded and practiced to support this transfer in student thinking that enhances their fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. However, this attention is an excellent investment that yields reading success for students well into their adult lives.

Reference:

McCormick, S., and Zutell, J. (2011). Instructing students who have literacy problems. (6th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

I agree that morpholgy is a huge component of word learning activities. What I see however is that many older students were not taught the foundation skills of decoding which are in Appendix A ([gs 17-24) of the CCCSS . They get to middle school or high school and cannot gain context clues or really delve into the important of morphology because somewhere along the line no one taught them to decode, no one taught them syllable division or the basic syllable types that form the structure of our language. I dealing with remedial students especially, we need to make sure the foundation is in place to support higher vocabulary learning and development.

I agree 100%. As a kindergarten teacher, I am really trying to start with that phonological awareness of word parts. Later in the year, we learn to decode those two-syllable words and compound words. It has been a huge disconnect for so many years and there is a gap for those students who were never taught to hear or look for those word parts. So many of our students are coming to us with a limited vocabulary because parents have stopped explaining words to their children and, in some cases, children are not even having conversations at home with their parents. It is becoming more and more crucial every year to teach “words”!

Having just read Three Simple Steps to Empowered Word Learning by Kenny McKee, I was surprised to read that the three steps to decoding a word should be in a sequence. I am used to having students work on K.I.M charts and use a 5 square format for understanding a vocabulary word (Word: antonym, synonym, sentence, illustration) as examples. But I never thought they should be done in an order. I will try this out next year.

Victoria, I think your strategy is one that is great for intentional teaching of new vocabulary. I use a similar strategy in my class when teaching academic vocabulary, especially in science and social studies. Tier 3 words that may not transfer but are highly important for specific content are best taught directly. The article adds a layer that allows students to learn from their own reading. I have not thought about the sequence of that either, and I appreciate how teaching the steps in sequence might unlock new words for my students this year. Great article!