Homework. It can be challenging…and not just for students. For teachers, designing homework can be a daunting task with lots of unanswered questions: How much should I assign? What type of content should I cover? Why aren’t students doing the work I assign? Homework can be a powerful opportunity to reinforce the Shifts in your instruction and promote standards-aligned learning, but how do we avoid the pitfalls that make key learning opportunities sources of stress and antipathy?

The nonprofit Instruction Partners recently set out to answer some of these questions, looking at what research says about what works when it comes to homework. You can view their original presentation here, but I’ve summarized some of the key findings you can put to use with your students immediately.

Does homework help?

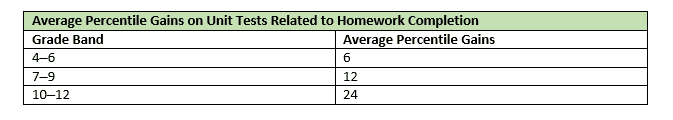

Consistent homework completion has been shown to increase student achievement rates—but frequency matters. Students who are given homework regularly show greater gains than those who only receive homework sporadically. Researchers hypothesize that this is due to improved study skills and routines practiced through homework that allow students to perform better academically.

Average gains on unit tests for students who completed homework were six percentile points in grades 4–6, 12 percentile points in grades 7–9, and an impressive 24 percentile points in grades 10–12; so yes, homework (done well) does work.[i]

What should homework cover?

While there is little research about exactly what types of homework content lead to the biggest achievement gains, there are some general rules of thumb about how homework should change gradually over time.

In grades 1–5, homework should:

- Reinforce and allow students to practice skills learned in the classroom

- Help students develop good study habits and routines

- Foster positive feelings about school

In grades 6–12, homework should:

- Reinforce and allow students to practice skills learned in the classroom

- Prepare students for engagement and discussion during the next lesson

- Allow students to apply their skills in new and more challenging ways

How Much?

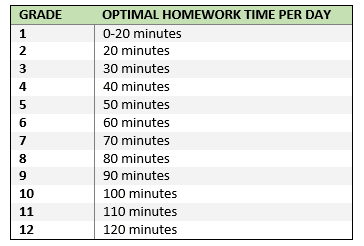

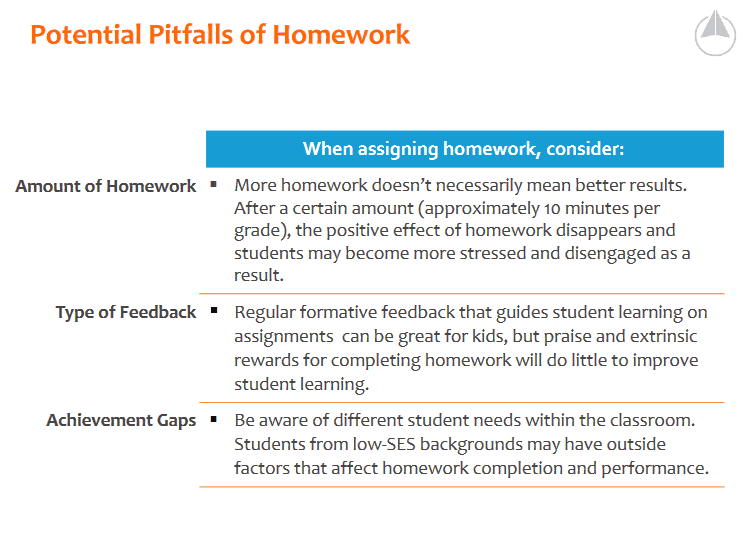

The most often-heard criticism of homework assignments is that they simply take too long. So how much homework should you assign in order to see results for students? Not surprisingly, it varies by grade. Assign 10-20 minutes of homework per night total, starting in first grade, and then add 10 minutes for each additional grade.[ii] Doing more can result in student stress, frustration, and disengagement, particularly in the early grades.

Why are some students not doing the homework?

There are any number of reasons why students may not complete homework, from lack of motivation to lack of content knowledge, but one issue to watch out for as a teacher is the impact of economic disparities on the ability to complete homework.

Multiple studies[iii] have shown that low-income students complete homework less often than students who come from wealthier families. This can lead to increased achievement gaps between students. Students from low-income families may face additional challenges when it comes to completing homework such as lack of access to the internet, lack of access to outside tutors or assistance, and additional jobs or family responsibilities.

While you can’t erase these challenges for your students, you can design homework that takes those issues into account by creating homework that can be done offline, independently, and in a reasonable timeframe. With those design principles in mind, you increase the opportunity for all your students to complete and benefit from the homework you assign.

The Big Picture

Perhaps most importantly, students benefit from receiving feedback from you, their teacher, on their assignments. Praise or rewards simply for homework completion have little effect on student achievement, but feedback that helps them improve or reinforces strong performance does. Consider keeping this mini-table handy as you design homework:

The act of assigning homework doesn’t automatically raise student achievement, so be a critical consumer of the homework products that come as part of your curriculum. If they assign too much (or too little!) work or reflect some of these common pitfalls, take action to make assignments that better serve your students.

[i] Cooper, H. (2007). The battle over homework (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

[ii] Cooper, H. (1989a). Homework.White Plains, NY: Longman.

[iii] Horrigan, T. (2015). The numbers behind the broadband ‘homework gap’ http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/04/20/the-numbers-behind-the-broadband-homework-gap/ and Miami Dade Public Schools. (2009). Literature Review: Homework. http://drs.dadeschools.net/LiteratureReviews/Homework.pdf