Many of us are familiar with this scenario: Our school’s leadership decides that equity is a priority, and we move to action. We read books, listen to podcasts, watch documentaries, and bring in consultants to facilitate us through difficult conversations, create a definition for equity, and talk about race. We are becoming more aware than ever of the ways society and our own institution perpetuate racism and inequity. There is a strong and wide commitment to equity, but most folks are left asking the question– But what can I do in my classroom tomorrow?

At Equity Meets Design (ExD), we believe the way that we can do equity on a day-to-day basis is to think of ourselves as designers as well as educators, think of our work as design work as well as teaching, and to make sure we’re using an equity design approach as we address challenges, make decisions, and plan instruction for our classrooms.

At the core of ExD’s work is the belief that racism and inequity are products of design, meaning they are the result of (design) decisions that people (designers) made when they created things. These things can be as seemingly small as forms we have students and parents fill out to as big as decisions about tracking policies in a district. The good news is that, since those things were designed, they can be redesigned, and the next time we can do it better.

But designing in this way is hard work, so we’ve been working to create a set of tools, frameworks, and processes that can support folks in being equity designers. (You can read an overview of our process here.)

While we firmly believe equity work requires working from the inside out, we believe personal work must be done in the context of your daily work, school/district-wide objectives, and the realities of your classrooms. There is no one-size-fits-all approach to equitable schools. Locally, each of our teams must decide how we identify who will be a part of the decision-making team for a project, how we define and frame the problems we’re working on, with whom and how we develop potential solutions, and how we roll those out. One part of the process we’ve seen be super helpful for folks as they transition to thinking about themselves as equity designers is the work they do (often not enough of) in identifying, articulating, and framing the problems they will tackle with their work.

Problems

Human errors manifest in the way we identify problems and create solutions. We often misidentify the problems we are trying to solve. We may even do a great job of solving the wrong problem. Sometimes we build things that don’t solve problems at all or make the problem worse.

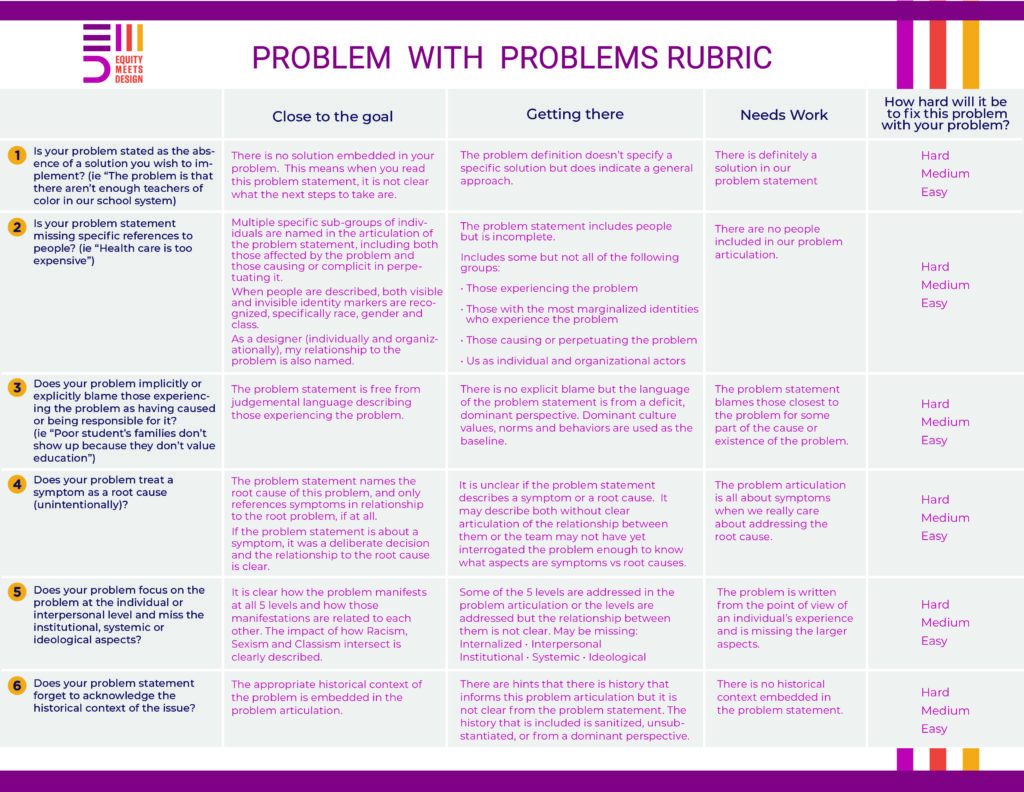

The way we go about defining (or not) the problems we are working on is an opportunity for an intentionally equity-centered approach. We have distilled what we believe are powerful insights about the common ways the process of defining problems and the definitions themselves can amplify oppression (problematic problem-definition 😉)–what we call the 6 Problems with Problems. They are as follows:

- The problem that you articulated is simply the absence of the thing you want to do or build or of the outcome you want to be true.

- The problem is articulated without referencing any people–those experiencing it or those creating or perpetuating it.

- The problem explicitly or implicitly blames those experiencing the issue for its existence, usually by framing the problem as deficiencies or flaws in a group of people.

- The problem that has been identified is just a symptom but is treated as a root cause.

- The problem is described at the level of individuals, absent institutional, systemic, or ideological factors that are also at play.

- The problem is described absent the history of how it came to be.

Let’s try an example. Imagine (or maybe you don’t have to) that one of your students consistently disrupts your whole-class math instruction by joking around, attempting to distract classmates, and even physically leaving her desk during the lesson. Our initial problem statement might be “I have a student with behavioral problems. I need to stop her from disrupting class and impeding the learning of her classmates.” This is a totally natural way to frame this challenge, but let’s see how the 6 Problems with Problems might help us think more productively about how to address this opportunity.

- The problem that you articulated is simply the absence of the thing you want to do or build or of the outcome you want to be true. This is true of our original problem statement. We’ve jumped to identifying a solution and ideal outcome without investigating the articulation of the problem itself. Our solution may not be solving the root-cause problem.

- The problem is articulated without referencing any people– those experiencing it or those creating or perpetuating it. We referenced one person, the student herself, and what we perceive to be the impact of her action on others, but who else is involved or affected? As the teacher, have we played a role in creating the situation? Would other students actually benefit from this student’s voice if used differently?

- The problem explicitly or implicity blames those experiencing the issue for its existence, usually by framing the problem as deficiencies or flaws in a group of people. Our problem statement implies the student is purely to blame, and we need to address the problems inherent in her behavior. How else could your frame your problem so blame isn’t solely placed on the student?

- The problem that has been identified is just a symptom but is treated as a root cause. We’ve identified the problem (and solution) as a behavioral issue, but what are the root causes of that “symptom?” If we want everyone to be focused on grade-level math content, what could we do to achieve that vision? Is it addressing unfinished learning so students have better access to content? Reducing “teacher talk time” to include more time for student discussion and engagement?

- The problem is described at the level of individuals, absent institutional, systemic, or ideological factors that are also at play. Again, our problem statement focuses at the individual level of the student, but we haven’t discussed or considered other factors that could be at play. For instance, has this student persistently been overlooked and ignored in class so that she feels this is her only way to engage? Have our own biases led us to assume that the student’s actions are normally disruptive rather than productive?

- The problem is described absent the history of how it came to be. The student’s actions in the classroom aren’t a random occurrence, and they don’t occur in a vacuum. What is the history that has led us to the current challenge?

This rubric was created to help us evaluate our current problem articulation and push us to a deeper, more historically nuanced understanding, all in service of making sure we have the best shot of actually solving the super complex issues we’re working on.

We encourage you to use the rubric to help refine a problem you’re currently working to define and/or solve.

For a deeper dive into the ExD process check out our online courses at courses.equitymeetsdesign.com.