Achieve the Core, powered by Student Achievement Partners, has offered free, high-quality, grade-level resources since 2011. For our latest tools and initiatives, visit LearnwithSAP.org.

-

New Resource

New ResourceEssential x Equitable Instructional Practice Suite™

-

blog

blogA Guide to Integrating AI for Deeper Literacy Learning

-

Popular Resource

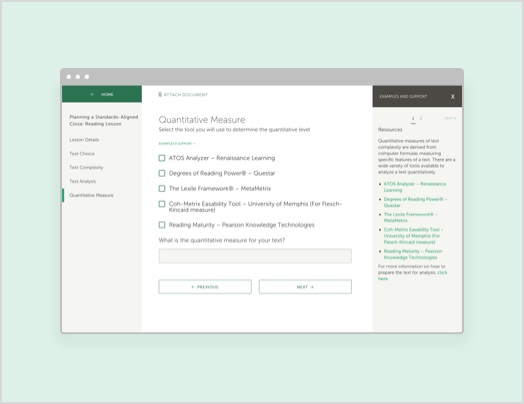

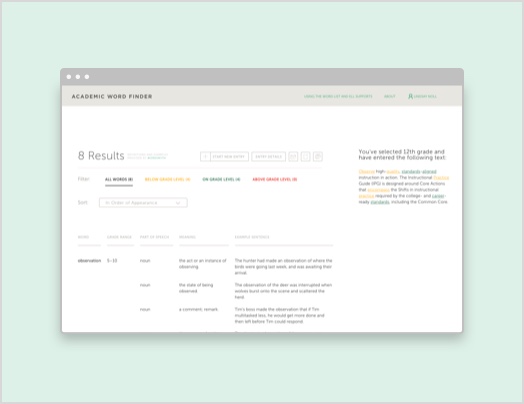

Popular ResourceText Analysis Toolkit

-

Webinar

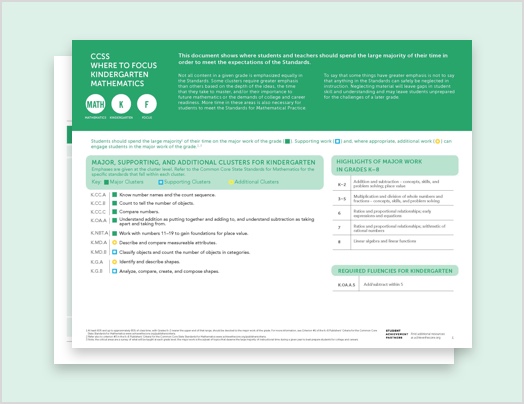

WebinarMath Milestones: The Math of Your Grade on a Single Page

-

New Collection

New CollectionSupporting Equitable Literacy Instruction

-

New Resource

New ResourceELA Planning Pathways

-

New Collection

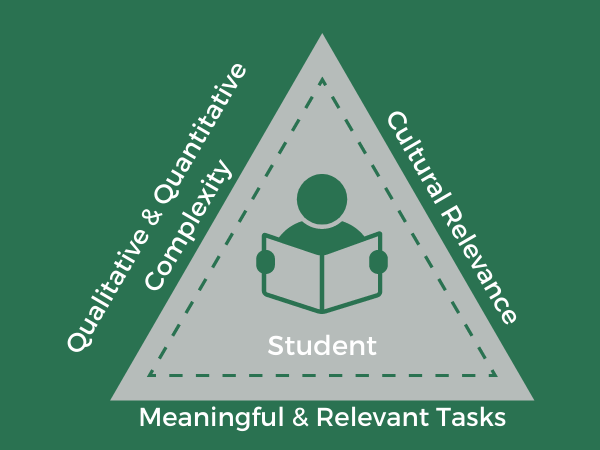

New CollectionPlanning and Reflecting with Culturally Relevant Pedagogy

.jpg)

.jpg)