During the 2017-2018 school year, Student Achievement Partners and the Council of the Great City Schools engaged in a collaborative pilot partnership with the kindergarten and first grade classrooms in a small group of Metro Nashville Public Schools. The goal? Leverage the existing structures and instructional resources in use in the classrooms, and focus on best practices needed to support early readers. The primary areas of focus for this work were amplifying foundational skills and using the read aloud block to build knowledge and vocabulary.

Amplifying foundational skills means several things, and guidance was provided accordingly. The number one focus was allocating enough time for whole-class instruction, student practice, and small-group instruction. Below you’ll hear one literacy coach’s reflections on the impact of increasing the amount of time spent on foundational skills.

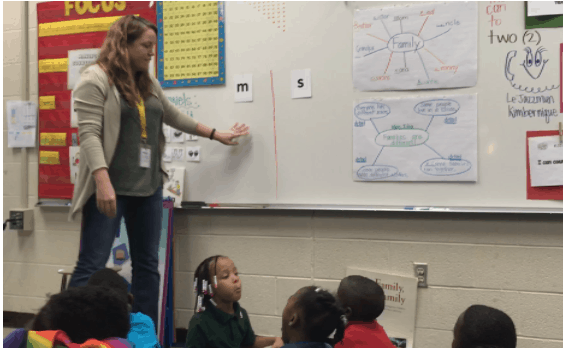

Lauren Wilson is the Literacy Teacher Development Specialist (LTDS) at an elementary school in Nashville, Tennessee. It is her responsibility to create an environment that supports young readers (and those that teach them). She works closely with teachers to build their capacity in literacy by modeling lessons, observing teachers, and sharing literacy district initiatives. She was the pilot lead for the work with Student Achievement Partners in her school.

How did you become introduced to the idea of extending the amount of time spent on foundational skills? What convinced you that this is a change you should make in your local setting?

As a new coach in my elementary school, I learned about the Student Achievement Partners pilot program from my principal during the summer. He asked for my opinion on the proposed expansion of the foundational skills block and I was completely on board. Based on our scores, we needed support in foundational skills. When meeting with the first grade team at the end of the summer, I was informed that they devote so much time re-teaching skills that should’ve been mastered in kindergarten. We needed to improve what we taught and when, to avoid inefficient re-teaching. Extending the amount of time spent on foundational skills would give our students explicit phonics instruction, practice with their new skills in using decodable readers, and eventually the ability to put their skills to use with any text. The extra time also would allow teachers to meet with more students for small group instruction to focus on the skills the specific students need the most support with. Following the guidance from Student Achievement Partners would help the teachers to be more intentional during small and whole group lessons. Not only would we have the support from administration to allocate time this way, but also the support from literacy specialists at Student Achievement Partners.

Prior to making the switch, about how much of class time in grades K-2 was spent on foundational skills? Was this what was recommended by the curriculum you were using?

Prior to making the switch, foundational skills were only taught during a 15-minute period each day. The small group time was really centered on guided reading. Although the term “word work” was included in our framework as something that teachers could do during small group lessons, many teachers really used the time to introduce leveled text. Students were not consistently reading decodable texts, regardless of their reading proficiency. The phonics piece was very brief during whole group and typically moved to an independent worksheet students did on their own.

Why do you feel foundational skills are critical to literacy development? Why is more time needed?

Some students are entering third and fourth grade unable to read and, at times, unable to identify letters or letter sounds. They do not have an understanding of foundational skills to access grade-level text as they matriculate through the different grade levels. Foundational skills are critical to literacy development, and are the basis of reading. Focusing on these skills has allowed our students to build the skills they need for reading systematically, starting with the youngest students. In the past, teachers had a skill from the scope and sequence document and taught it. Due to limited time, sadly, teachers felt pressured to move on. Focusing on teaching for mastery, and following up with assessment each week, has allowed teachers to hone in on the specific needs of students. They are able to identify the specific areas such as sound identification, blends, and vowels that are a concern and pull students to small group instruction for re-teaching and more practice.

How did you convince your fellow educators that a shift in time allocation was needed? Was there any reluctance to making the change?

Being at a new school this year, it was very challenging at first. I was a new face also pushing a different approach to the typical “guided reading” block that has been instilled in them since their first elementary college course. While it helped that I had a principal who was completely supportive of this work, I think my ability to convince teachers really came from sharing data and scores with teachers. At the beginning of the school year, we completed a diagnostic screener that was provided by Student Achievement Partners (originally from Marilyn Adams’ book Phonemic Awareness in Young Children). The diagnostic screener assessed foundational skills and the results indicated that students entering first grade were not prepared to access skills. This also meant that so many students were behind academically in the older grades due to not having the basic, foundational skills. The numbers proved that how we were teaching wasn’t effective. The new approach of focusing more time on phonics and less on the typical “guided reading” had teachers very reluctant. “How can this work? Focusing on phonics that long?” The diagnostic screener confirmed that the way we were teaching was not meeting the needs of our students–and they were suffering.

Can you give examples of the kinds of work/activities you pursue during this extended foundational skills block?

Learning should be fun! Our teachers teach by incorporating kinesthetic activities into the foundational skills components of the lesson. We incorporated games and activities from Marilyn Adams’ book, “Phonemic Awareness in Young Children.” Our Journeys Decodables have been used and students are so excited when they realize they are reading. We also began a weekly dictation that served as a quick assessment of taught skills each week. The weekly assessments in kindergarten and first grade allow teachers to assess weekly skills, track progress, and identify where re-teaching is needed.

When I spend time in classrooms during walk-throughs or modeling lessons, I’m noticing students making connections between sound and spelling patterns and printed text. My Dean of Instruction shared with me that all students made progress on the recent benchmark assessment. Although all students aren’t meeting proficiency benchmarks yet, we believe the progress shows our adjustments are working. We use Fast Bridge, a progress monitoring tool, to assess student knowledge in math and reading. In regards to reading, the number of high-risk students in grades K-1 decreased from 63% to 32%! Our low-risk student percentage increased from 10.8% to 40.8%! First graders who were high risk decreased from 42% to 38.7%. I truly believe that we will continue to see a significant improvement with reading scores by focusing on foundational skills.