In a recent blog post, we identified five key literacy accelerators and shared some early learnings from our examination of the research on how personalized learning might accelerate students’ literacy outcomes, and how to do so equitably and justly to the greater good of all students. While we acknowledge the potential triumphs of personalized learning, we note these are as yet unrealized. They are also matched by known perils including a troubling track record that has resulted in locking too many students into below-grade-level, mind-numbing work.

We are following up with a set of principles educators can consult right away as they decide whether, what, and how to include personalized instruction—human or technology-enabled—as an adjunct to the central work of the English Language Arts class.

Time is a scarce commodity in educating students—now made more compressed by months of school closures. With greater variability in the experiences of returning students, how can we best accelerate all students’ learning, amplify what matters most, and invest in students’ social-emotional development so they engage in schoolwork? Whether school has started back with students learning in buildings, remotely, or through rolling closures, all students in every learning community need to be engaged in challenging study. What has always been important is especially important now.

Anything that distracts from the focus on students learning to read, reading and listening to content-rich texts widely and deeply, and responding to what they read through lively discussions and in writing will need to be stripped away. Tools and techniques that promote these activities should be given priority. Limiting work to a focus on the essentials will enable students to engage more profoundly with content-rich texts and create opportunities to provide students with needed supports and scaffolding. Focusing on the work that matters most promotes well-being and allows students to thrive.

Personalized learning can play a role here, but beware the pitfalls.

Given the months students have been out of school and socially isolated, coupled with the complicated realities many students are facing, it can be tempting to double-down on traditional leveled text instruction—a particularly pernicious form of personalized learning. It limits students to reading texts at their designated independent reading levels and to reading texts they already know how to read without teacher support. Seductive, but destructive. For a sizable number of students, this translates into reading a restricted range of lower-than-grade-level complex text (one day on one topic and another day on another topic) that will hinder, rather than accelerate, their literacy development. For students to become literate participants in the world around them with the ability to deploy and understand English in integrated, holistic, and flexible ways, they need and deserve regular access to grade-level complex texts in the company of their peers. They also need lots of time to independently explore particular topics (influenced by their individual interests at times) by reading multiple texts at various complexity levels. Otherwise, students won’t grow the vocabulary and knowledge they need, or learn how to deal with complicated syntax or subtle cohesive links in texts.

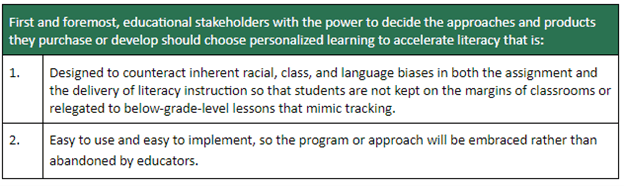

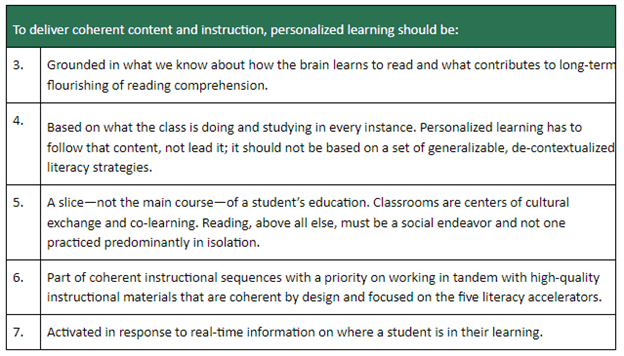

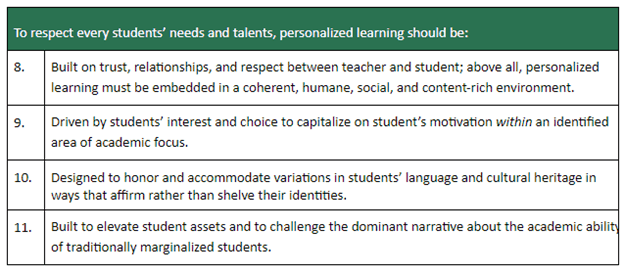

Core principles for personalized learning approaches or products to accelerate literacy

Regardless of the aspect of literacy or the nature of the personalization, our developing thinking has pointed us toward a set of core principles that must be addressed to do any personalized learning well.

Translating the core principles into “Do Nows” with literacy instruction

How might these principles translate into ways personalized learning can help with literacy right now to mitigate some of the pressures teachers, students, and families are facing? What kinds of initiatives are best set on the “explore these ideas later” stack? What should be avoided at all costs? The examples that follow are proxies for the kinds of decisions we’d urge stakeholders to make and are by no means exhaustive. This directional guidance will be fleshed out more in the longer report of findings (early 2021).

Personalized learning can be used right now in literacy to:

- Provide practice in various forms for mastering phonemic awareness and phonics skills to the point of automatic word recognition. The research on foundational skills and their place in securing reading progress is clear. It is also clear there is wide variance in how much exposure and practice different students need for mastery. Note, this experience can be tech-enabled but must be accessible to all students in any setting, indicating materials may need to also exist in physical form, e.g., paper and pencil or free-standing device. (Supports foundational skills. Accounts for all principles.)

- Provide fluency practice with grade-level readings connected to the instructional focus of students’ classes or student interest. For older students, double duty can be accomplished by positioning such practice as performance and public speaking. (Supports foundational skills and speaking about text and public speaking facility. Accounts for all principles.)

- Assess all foundational skills progress in all areas, providing feedback and additional practice as indicated by results. Assessments must be lightweight and administered frequently. (Supports foundational skills mastery. Accounts for principles 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 10.)

- Provide access to a wide volume of reading to build knowledge and vocabulary. Texts and other media must be abundant, exist at a variety of complexity levels for universal and independent student access, and be clustered around topics that connect to what the class is studying and/or student interest. (Supports growing vocabulary and knowledge. Accounts for principles 1, 2, 10, and 11 especially, and does not activate principle 7.)

- Provide opportunities for writing and discussing text and textual evidence connected to topics being studied. In a time of disrupted learning, it is imperative that students have a variety of ways to collaborate with one another and stay connected to the life of the classroom. (Supports access to complex text. Accounts for all principles, with 1, 2, 4, and 8 most critical.)

What we really need is that “hard reset”—to reimagine how we do school for all students.

In sum, every student is entitled to the “good stuff”; every student must be regularly engaged in reading and thinking about rich, grade-appropriate content and get to do so regularly in the company of peers. Every student should get what they need when learning is personalized. How can both these conditions be met consistently, within the same classroom in ways teachers can implement and sustain, and students reap the benefits? One obvious answer is to provide the human and material resources to accomplish both—to invest smartly and generously in educating every student to their intellectual potential—something we have yet to do as a nation. Stay tuned for a paper in early 2021 that provides more detail and a way forward on the potential intersections between the literacy accelerators and personalization.