Lorraine Griffith co-presented a webinar focused on building reading fluency. Webinar participants were encouraged to ask questions via chat submission. The following questions were some of the more commonly asked. David Liben will follow up with another blog focused on the remaining questions. The full webinar can be downloaded here.

1.What fluency strategies do you recommend for younger students? For older students?

No matter what the age, multiple reads with challenging texts follow a similar routine:

- Model a fluent read

- Echo read

- Choral read

- Partner read

- Individually read

Finding opportunities for the younger crowd is easy. Have you ever read a book like Chicka Chicka Boom Boom to a kindergartener and had her NOT repeat the recurring phrases in the text? When these repeated phrases are captured on a chart, you have your first fluency texts. Posting poetry such as “Now We Are Six,” encourages students to expressively interpret poetry.

Song texts (with students reading along) such as “The Crawdad Hole” and “Aiken Drum” are natural opportunities for fluency development because songs are meant to be sung repeatedly. Songs with choruses give students instant success in much the same way that repeated phrases in a text keep pulling children back to a favorite book.

The role of punctuation in prosody is also teachable with the younger crowd. When students practice pausing or raising their voices in a question, sparked by the symbolic cues of a comma or question mark, they learn the art of phrasing. To teach this cuing system in a simple, focused way, Louisa Moats suggests writing the ABCs like this: A B C, D E F, G H I J ! K? L M N. O P Q? R? S T U V W, X Y. Z! Students love to chorally read the ABCs. Later, they move the punctuation marks around for different dramatic effects. Projecting and repeatedly reading a book like Yo! Yes? with only 34 words, applies punctuated-inspired expression to a conventional text.

By grades two and three, students can tackle first-person, high-interest excerpts from complex texts, such as Because of Winn-Dixie or Ruby Bridges Goes to School. When tied to units of study, folk songs such as “Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around” build knowledge and historic empathy. When students read and perform a serious, topic-related poem or a funny Bruce Lansky poem, they learn the love of poetry.

Note for grades two and three: Consider doing a “fluency boot camp” during your intervention block for the first six weeks of school. With a school-wide focus on reading a variety of fluency texts including songs, fun poetry, short passages, and reader’s theater, you can minimize summer slump. Students begin the year with a jump-start on grade-level reading.

In grades four and beyond, the previously mentioned text types are appropriate with the natural progression to a higher text level. Great speeches can be introduced. To grow expectations for performance quality, assign a speech such as Sojourner Truth’s “Ain’t I a Woman.” After students have spent time rehearsing, show them a dramatic interpretation of the speech such as this one by Cicely Tyson. Suddenly, classroom actors are born and the work takes on new life.

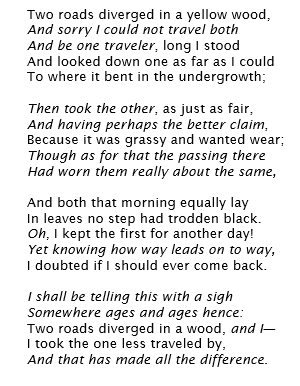

Poetry work with a poem such as “The Road Not Taken” gives students opportunities to see how the directive “read to the punctuation” is tied inextricably to comprehension. Contrast the meaning created by this thoughtful, punctuation-oriented phrasing with the students’ tendencies to pause at line breaks.

As students perform poetry with intentional pauses and arcs of phrases, guided by the punctuation instead of line breaks, understanding will come.

2. How does Readers’ Theater build fluency? How do you recommend implementing it in your classroom?

Readers’ Theater authentically motivates students as they engage in preparation for performance. Students build fluency as they focus especially on phrasing and expression. Rehearsing their own parts independently, they eventually carefully track others’ parts for entrances. Set in a rich context, challenging vocabulary accrues as students read their own parts repeatedly and track the others’ parts.

A simple weekly routine for initial implementation goes as follows:

- Copy a class set of scripts.

- Assign nightly homework or use five minutes of class time

- Monday: focus on accuracy, word pronunciation

- Tuesday: focus on phrasing

- Wednesday: focus on expression

- Thursday: focus on rate, volume, and cues for a smooth Friday performance

- Group students into performance groups on Thursday – rehearse for 15 minutes

- Perform on Fridays.

- Use the script for another week and allow students to switch parts and take the part to a new level.

An online search yields free resources such as Aaron Shepherd’s and Dr. Chase Young’s work. Tim Rasinski has gathered an extensive list of resources here.

3. When using songs and poetry to build fluency, how long should students spend working with a particular text? How do you ensure they’re building fluency and not simply memorizing?

At the beginning of fluency work, it may be difficult to know exactly when students are finished with one text and ready to move to the next. When working with songs or poetry, memorization is my cue to move on. When they are beginning to say a poem or sing a song without looking at the text, I know it’s time to start the next one. There are so many poems and so many songs to choose from, why limit exposures and opportunities?