Having high quality data is critical to making smart decisions. Without evidence of “what’s good” and “what works” we’re essentially choosing blindly when it comes to instructional materials.

We, as a nation, do not have strong evidence about the effectiveness of different curricular materials, how they’re being used, or even where different materials are in use. In 2015, it was reported that free EngageNY curricular materials had been downloaded more than 20 million times by educators in a multitude of states, but how were these materials being used and with what results? Outside of New York, we really don’t know or have any way of tracking effectiveness.

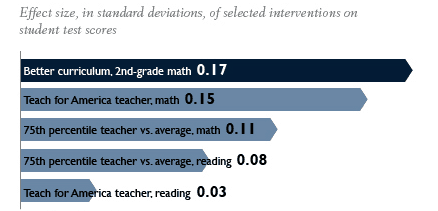

A 2012 report by the Brown Center on Education Policy at the Brookings Institution called Choosing Blindly highlights exactly how much we don’t know about where and how instructional materials are being used. This is concerning for a number of reasons, the first of which is that instructional materials affect student learning in a way that rivals differences in teacher effectiveness. In an Institute of Education Sciences (IES) study (one of the few studies looking at the effectiveness of textbooks), researchers compared the effectiveness of four elementary math curricula. Second grade students using one curriculum scored .17 standard deviations higher in math than those using another curriculum.1 By comparison, in a review of 10 studies of teacher effectiveness, students who had an above-average teacher – one in the 75th percentile in terms of effectiveness – only scored between .08-.11 standard deviations higher. The Brookings report posits that instructional materials may actually play a sizeable role in teacher effectiveness and in the variability of teacher performance: it’s much harder for a teacher to succeed if his or her materials are a hindrance.

Data for this graph was compiled from three studies: one on the effect size of different textbooks,1 one on the effect size of high-impact teachers,2 and one on the effect of Teach for America teachers.3

The report points out that we know next to nothing about how materials and textbooks are being used at the school and classroom levels. In the past, many states had a state-approved list and districts and schools were required to show that the materials they purchased were on the list. In contrast, most states, even if they have a recommended list, no longer require purchasers to report what they use. Thus we’re missing crucial pieces of the puzzle in determining why some schools and districts are high-performing and others aren’t. In addition to curriculum purchases, in the age of OER, many teachers are finding their own materials on the internet, supplementing or even completely replacing their school’s curriculum. Since we aren’t tracking usage, however, we have no evidence on the effectiveness of these materials.

The report recommends three strategies to start obtaining better information on instructional materials:

- States should collect data from the school districts’ purchasing departments on materials ordered each year.

- Districts should be surveyed about the materials used in their schools to obtain a better picture of how curricula are implemented.

- States should periodically survey a sample of teachers to see if they’re using purchased materials or how what they’re using differs from what was adopted by their school.

Of course, there are limitations to what the data collected by these methods can tell us. Instructional materials that are effective in one district may be ineffective in a district with different student needs. Teachers may not feel comfortable admitting that they aren’t using the purchased materials. Different schools using the same textbook may have different outcomes depending on how much professional development they give to teachers on how to make the most of the curriculum. In order to make evidence-based decisions about instructional materials, however, the fact remains that educators and administrators need better data on what works.

Rubrics like the Instructional Materials Evaluation Tool (IMET) and the EQuIP Rubric (for lessons and units, respectively) can start filling the knowledge gap by pointing to evidence of Common Core alignment (or highlighting the lack thereof).

Footnotes:

- Roberto Agodini, Barbara Harris, Melissa Thomas, Robert Murphy, and Lawrence Gallagher, Achievement Effects of Four Early Elementary School Math Curricula: Findings for First and Second Graders (NCEE 2011-4001), Washington, DC: National Center forEducation Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S.Department of Education (2010).

- Eric A. Hanushek and Steven G. Rivkin, “Generalizations about Using Value-Added Measures of Teacher Quality,” American Economic Review 100(2): 267–71 (2010).

- Paul T. Decker, Daniel P. Mayer, and Steven Glazerman, The Effects of Teach for America on Students: Findings from a National Evaluation, Princeton, NJ: Mathematica Policy Research, 2004.