For many years, one succinct statement guided our work at Student Achievement Partners: “Academic standards are a promise of equity. When every student is expected to learn rich content, and is supported every day in doing so from kindergarten to high school graduation, we deliver on that promise.” This statement was designed to speak to the kind of academics that all students deserve, and to position standards as integral to meeting that goal. Today when we read that call to action, we recognize that it centers standards over students.

We came to Student Achievement Partners (SAP) believing in rich content and grade-level work for all students—and were hired as content specialists who had math- and literacy-specific experience. As white, cis women educators, we were reinforcing the idea of standards as equity, absent attending to our own identities or the cultures, languages, and identities of students.

Access ≠ Equity

In past conversations about instructional equity, we’ve often focused on getting all students access to—and support to succeed with—meaningful, grade-level work. We thought if we could get all students “the good stuff,” we’d move a long way towards more equitable experiences and outcomes.

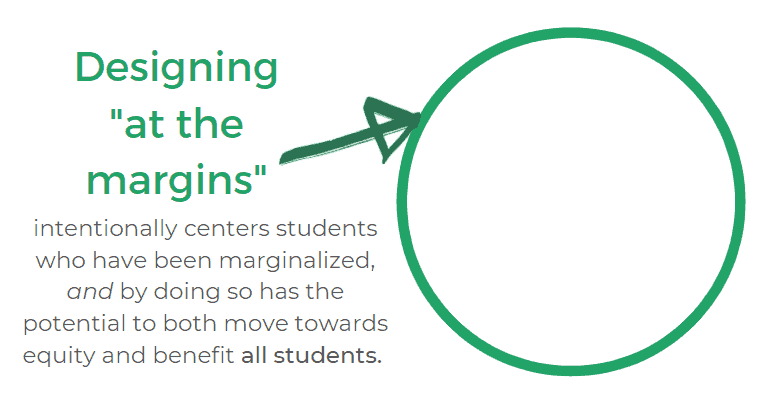

All students having access to grade-level work really matters, but we’ve learned that when we focus on the wide net of access, we don’t design specifically for students who have historically been pushed to the “margins” of the education system. Our friends at Equity Meets Design describe it this way: “If we can create solutions for those who are farthest from power, who are most proximate to the problem, we can learn to not just solve the problem for everyone but create a better reality for all” (see the Curb-Cut effect).

By centering students who are and have been the most underserved in our work, we’re not only focused on specific students’ unique gifts and identities, but we are also more likely improving experiences for all students. In fact, by ignoring who specific students are, we often ignored the systems, structures, biases, and experiences that marginalized students in school in the first place.

Narrowing Our Focus

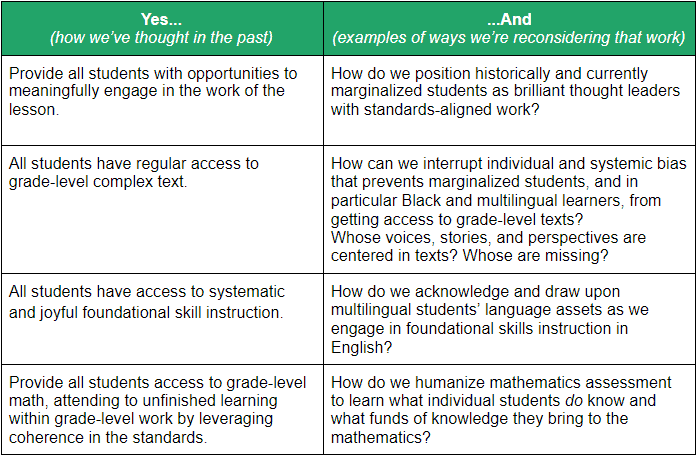

Across the country, we still have a long way to go to ensure that all students get the chance to experience grade-level work: far too many students are denied complex texts through use of leveled reading groups or tracked into below-grade-level math, for example. But we also know that for grade-level work to be identity affirming and in service of a more just world, we need to change. We’re reimagining how we support all students to thrive by narrowing our focus.

For us at SAP, this has meant shifting the way we think about who we are designing for and intentionally centering our work on Black students and multilingual students who are learning English. The decision to name these students as central to our design processes is based on the specific historical context of education in this country—a history of schools that were not built to recognize and foster the inherent brilliance of these, and many other marginalized, students due to centuries of white supremacy culture.

In our work, we’ve seen that naming specific students we want to center gets us a lot further, faster…and it also raises a lot of new questions.

- How do we attend to intersectionality (via Kimberlé Crenshaw) while centering parts of students’ identities? How do we ensure we are not approaching Black students and/or multilingual students as monoliths?

- What specific content, supports, mindsets, structures help Black students and/or multilingual students learning English to thrive?

- What supports do educators need to be able to make changes in classroom practices to support Black students and/or multilingual students learning English?

- How do we design new, or adapt existing, resources to attend more intentionally to Black students and/or multilingual students learning English?

Resources we’ve found helpful: If you want to Design at the Margins, Start with Yourself, The Complexion of Teaching and Learning

Interrogating Ourselves

Sharpening our focus on Black students and multilingual students learning English—and transforming the work we do to support those students—has pushed us to further consider our own identities. We constantly reflect on the ways we are showing up as white, monolingual people and how we are either reinforcing or working against dominant ways of being. We know we must continuously be intentional about recognizing and naming white supremacy culture and English dominant lenses in both how we work and what we produce through our work.

This has helped us to commit to a few ways of working:

- Continually examine our own biases, positions in the work, and ways we are upholding white supremacy culture.

- Partner with BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) and multilingual folx in our work through collaboration and co-design.

- Elevate the voices and ideas of BIPOC and multilingual folx.

Resources we’ve found helpful: The Characteristics of White Supremacy Culture, Equity Meets Design (free course)

Changing The Work

Approaching the work from a student identity lens and ensuring we are conscious of how our identities influence that work has meant digging further into the rich depth of work from scholars and practitioners who have made this their life’s work (Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings, Dr. Rochelle Gutierrez, Dr. Gholdy Muhammad – just to name a few). This has elevated lenses that have been previously missing or underutilized. As we’ve worked to better understand Culturally Relevant Pedagogy, we’ve reflected on where our focus on math and literacy content fits within the framework…and where it falls short. For example, we now consider the “who” more frequently and intentionally (Who am I? Who are the students I am designing for? What are my students learning about their own cultures, as well as others?), and ask ourselves “so what?” (Why does this matter? How does this advance social justice?). While Academic Achievement is one critical component of Culturally Relevant Pedagogy, we have started reflecting on how our work attends to Cultural Competence and Socio-Political Consciousness.

This has meant reconsidering (and reconsidering again as we learn more) how we’ve thought about the work:

Looking Ahead

We know it is lifelong work to focus on students alongside content and recognize, as well as work toward, dismantling white supremacy and dominant ways of being. We have made mistakes—and will continue making them—as we work to hold ourselves accountable. We don’t have all the answers and see every day as an opportunity to recommit to this work through our actions. We hope you will join us in doing the same!

To learn more about the ways in which SAP is working to dismantle white supremacy culture in our organization and sharpen our focus on racial equity, look out for additional posts in this series.