Editor’s Note: Author Adrienne Williams co-presented a webinar focused on scaffolding strategies. Webinar participants were allowed to ask questions via chat submission. The following questions were the most commonly asked regarding elementary ELA scaffolding. The full webinar can be downloaded here.

1. Teachers are concerned that students will become frustrated or disinterested when faced with challenging texts with which they may not initially be successful. How do you help students persevere? What strategies keep motivation high even when students struggle?

There are two key levers for getting reluctant readers to engage with text: interest and access. By providing students with a topic that is high interest, students start with some degree of buy-in. To prepare them for the complex text, consider building them up to it by giving them opportunities to build knowledge and vocabulary with lower texts before presenting them with the complex text. Be careful, however, not to limit their exposure to just lower-level text. The goal is to hook them with the topic, allow them to feel successful, and then present the challenge of the complex text with the frame that they have the tools to work through it.

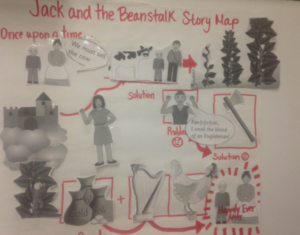

Providing an access point for the complex text is another way to allow students to feel some initial success. Determine what aspects of the text they can connect to and understand. Start small! You may start out focusing on story elements and, over a series of lessons or repeated reads, get to focusing on the evolution of characters throughout the text. With repeated practice and the opportunity to feel some success by scaffolding up to the hardest task, even the most reluctant readers will learn they can tackle any text.

2. How should teachers allocate their time to different instructional strategies? How should teachers determine what percentage of their reading blocks should be allocated to each type of instruction?

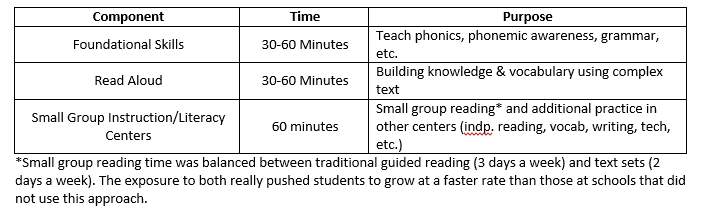

When considering how to allocate time between all the different components of literacy, it’s important to keep in mind the amount of instructional time you have, specific student needs, and your role in facilitating learning. Ideally, the time you spend on each would be flexible based on what your students need. The important thing is that you provide them a balance and variety of opportunities to engage in each. That being said, I’ve found that having a set amount of time daily for foundational skills, read aloud, and centers is useful.

3. How can teachers make this doable in a whole-class setting? It can be challenging to deal with a lot of different reading levels all at the same time. Additionally, pre-teaching and scaffolding is time-consuming. How can you make it all work?

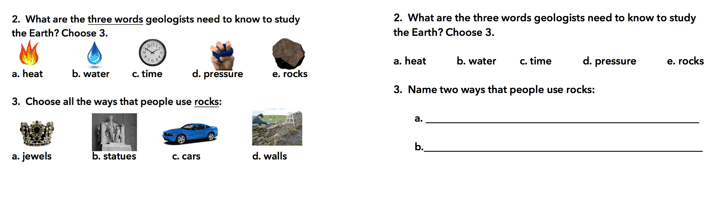

In order to use your planning and instructional time most efficiently, consider which TWO strategies you can use for any lesson to provide better access. Think of one strategy for during the reading and the other to provide access to the task you’re asking students to do. When choosing which strategies to use, think about what will benefit the most students. During reading, that could be a visual anchor chart or visual vocabulary cards. When considering the task, only make two versions: scaffolded and non-scaffolded. My scaffolded student work includes more visuals and vocabulary cues. My non-scaffolded is more text heavy.  As you get better at planning for your varying ranges of students, it will be easier to make changes and offer more options of student tasks. Collaborate with your special educator or reading specialist to get a list of go-to ideas.

As you get better at planning for your varying ranges of students, it will be easier to make changes and offer more options of student tasks. Collaborate with your special educator or reading specialist to get a list of go-to ideas.

4. The reality is that many teachers are working with what they have: leveled readers. How can they ensure students have complex texts when they must use the readers supplied in their curriculum?

When you have to stick with what’s provided in your curriculum, which in most cases is leveled readers, you have to get creative on how to incorporate complex text.

- First: Consider what instructional time you have to dedicate to complex text. Are there days when you don’t have to use the readers? Could you fit in two days a week with complex text?

- Next: Identify resources from which you can pull complex texts for your students. Check the books you already have in your library; ask your colleagues. Some of the best supplemental articles and text sets I’ve found are from these three resources:

- Readworks.org (free)

- NewsELA (free & paid pro license)

- Achieve The Core (free)

- Last: Create your rationale for using complex text so that when your administration asks why you’ve done something differently, you can justify it based on research and student data.

- Article: Why Complex Text Matters

5. Can you share strategies for effective read-alouds? How often should you do them?

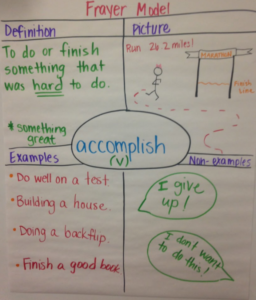

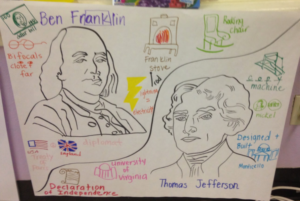

A read-aloud is only as effective as the effort you put into planning it. Planning is the most important aspect of doing a read-aloud because it focuses your lesson, aligns your questions, and dictates your task. Once you have identified the ‘big idea’ of the lesson, or what you want students to take away, consider how you will provide them access to the text. Because you’re already reading it aloud, the next most effective strategy is to provide a visual anchor and/or focus on key vocabulary. This can be done by using various types of anchor charts, picture vocabulary cards, and using props.

Next, make sure that your questions are targeted and in service of your big idea. Last, determine how you will assess student understanding. Each part of the lesson needs to be strung together in service of what you want students to walk away with. In terms of how often you should do them, it depends on the unit you’re doing and the content. There is no right or wrong number. If you have the flexibility, consider doing three read-alouds a week and on the other two days give students a chance to do a close read, gain content through a hands-on experience, or incorporating writing in response to text.