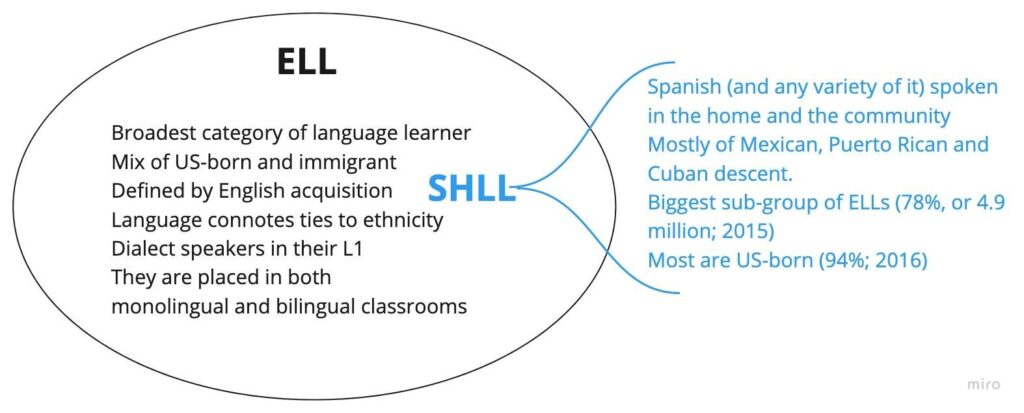

I recently spoke with a group of upper-elementary teachers in Texas about their students who are simultaneously learning English and Spanish. See, I’m often brought in as a content expert on English Language Learners (ELLs), which gives me a platform to help teachers unpack the labels that are used to describe students. We did a think-pair-share on the graphic below to explore whether Spanish Heritage Language Learners, which are the largest subgroup of ELLs in the country, fit into the ELL label as expected. Then, we discussed whether it made sense to them to refer to this population from an English-deficit perspective (e.g., an ELL highlights what students don’t have, and even that isn’t true since many ELLs claim English as their first language; García & Kleifgen, 2010). Jaws dropped. Eyes glanced. Questions arose: “So when I say, ‘they don’t have the language’, I’m actually contributing to a deficit narrative about my ELLs?” Cue face-palm emoji!

The purpose of this post is to re-examine the harmful labels used to describe bilingual learners and what instructional implications a shift in terminology can do to make space for linguistic empowerment in our classrooms…even if (especially when) you teach ELLs in your English-only classroom.

Here are some questions to keep in mind as you dive into this post:

- How can educators lovingly and thoughtfully support our bilingual learners if we continue to see them and to speak about them as lacking?

- What steps can we take to alter our speech around bilinguals to affirm their rights to language and to their access to an equitable education?

Who are Spanish Heritage Language Learners (SHLLs) and what do we know about them? An SHLL is “a language student who is raised in a home where a non-English language is spoken, who speaks or merely understands the heritage language (in this case, Spanish), and who is to some degree bilingual in English and the heritage language,” (Valdés, 2001; p. 38). You know the student: they often have strong ties to their heritage vis-a-vis both the language they speak and the cultural references they use. SHLLs make up 78% of ELLs, marking them as the largest subgroup in the category of language learner (US Census, 2015). Since the turn of the century, there’s been a steady rise in US-born bilinguals (think 2nd- and 3rd-generation Latinxs) whose home language practices are dynamic and draw upon both English and Spanish languages.

With a working definition in place, let’s probe how a narrative of lacking acts as a discursive slight-of-hand to position SHLLs as in need of remediation (Flores & Rosa, 2015; Gutiérrez & Orellana, 2006). To begin, they are often labeled as “underachieving” and “lagging behind” their monolingual peers. SHLLs’ overwhelming representation in low-resourced families compounds the reality of Spanish as a low-prestige language here in the US. All of these societal forces place acute social pressure on the students (and their teachers) to accelerate learning on both academic and linguistic grounds, and that pressure has not resulted in better student outcomes (NAEP, 2019). A Latinx youth sums up her lived experience as not belonging to either culture or country: “In school I was labeled as Mexican, but to Mexicans I am an American….You may never be fully embraced by either side,” (a quote from an anthology by Carriera & Beeman, 2014). You may not realize it, but continuing to refer to this student as an English Language Learner carries with it the baggage of decades of institutional failure and blaming the student (and their “not-having-language”) in ways that matter deeply to the important social and linguistic justice work that lies ahead.

“What is taught can only be meaningful if to whom we are teaching is clearly understood.”

María Luisa Parra, 2013

There are ways big and small that you can redress the deficit framing described above. First, I recommend being intentional with how you refer to this student. Even if your district refers to them as ESL or ELL students, you can offer: emergent bilingual, multilingual learner, or Spanish Heritage Language Learner. Although the new term will feel awkward in your mouth at first, every time you use it, you send an important message to your community that affirms the students’ rights to their language and culture. Instructionally, re-consider the sorts of genres you select from and how you can integrate more Latinx-centered text types (e.g.: testimonios, biographies of Latinx icons, poems). Use book lists like Latinxs in Kid Lit to begin your search. Another important area of change is in how we assess SHLLs: demand that Spanish assessments be administered for fidelity of tracking Spanish literacy growth. I have done some work with University of Chicago’s STEP Español reading assessment: it is a standards-based formative Spanish reading assessment for students in grades K-3.

For bilingual teachers, re-consider your classroom language allocation policy to tip the scales in favor of Spanish-medium instruction. Such an effort marks a radical commitment to your learner’s rights to their own language. And if an administrator (or parent) questions whether their growth in English will suffer, lovingly remind them that decades of research point to the interrelationship between language development in the home and new language. If you share a vision of equity for SHLLs that includes helping them become confident and competent members of their classrooms and in society at large, then making these adjustments will seem like the sensible (and ethical) thing to do. Learn more about how you can partner with me to bring linguistic justice to your SHLLs by visiting www.languagematters.org.